Torfi H. Tulinius is usually immersed in Icelandic medieval literature, in particular the Icelandic sagas. He has a passion for Iceland's literary heritage and the many different sides of the sagas that can reveal themselves depending on how you read them. What is more, the sagas are his livelihood. Torfi is a professor of Icelandic medieval literature at the University of Iceland, so spends most of his days poring over these texts. He researches Icelandic medieval history by considering the sources through different lenses. Sometimes he is a literary scholar, looking at the narrative, the texts themselves and the symbolism, critical reception of the sagas at different points in history, or sociological factors. Sometimes he takes a more historical approach, looking at the reality behind the narrative and contemporary events. Sometimes Torfi focuses on the characters, their psychological motivations and the complex relationships between them. Besides all this, Torfi also teaches a range of courses on medieval literature at the University of Iceland and the UI Continuing Education Institute.

His current research explores the link between social inequality and anxiety, as it appears in the sagas. Torfi knows that the Icelandic sagas are open to endless interpretations and at the moment is reading Laxdæla saga with the aim of finding out whether anxiety about losing social status could lead to violence.

Conflict between a slave-woman and a wife in Laxdæla saga

"I was reading Laxdæla saga, specifically the chapter about the arrival of the slave Melkorka in the household of Höskuldur Dala-Kollsson. He had bought her on a trip to Norway and took her into his bed on the journey," explains Torfi.

"What I became interested in was the reaction of Jórunn, Höskuldur's wife, and how the author describes that. At first, she doesn't appear that bothered, since her husband sleeps with her after arriving home, not his new concubine. Jórunn's treatment of Melkorka becomes colder when Melkorka's son is born, since he is a handsome child and Höskuldur loves him dearly. A few years later it transpires that the concubine is an Irish princess, meaning that the boy is of royal blood. This is the last straw for Jórunn and she violently attacks Melkorka, who fights back," says Torfi.

Laxdæla saga describes the incident, which would no doubt be defined as domestic violence nowadays.

"A little later, when Jórunn was going to bed, Melkorka helped her off with her shoes and stockings and laid them on the floor; Jórunn picked up the stockings and started beating her about the head with them. Melkorka flew into a rage and struck her on the nose with her fist, drawing blood. Höskuldur came in and separated them."

At one point the narratives of the sagas were described rather flippantly as "farmers fighting", but as Aðalheiður Guðmundsdóttir, professor of medieval Icelandic literature, says on the Web of Science, women often play a significant role in the sagas. This is certainly the case for Laxdæla saga, as the above example shows. Aðalheiður explains that the women in the sagas either urge the men to take revenge or act as mediators, thereby directly influencing the course of events. Many of the heroines of the Icelandic sagas have become symbols of exceptional Icelandic women and Laxdæla saga provides excellent examples.

Torfi believes that it makes most sense to think of Jórunn's behaviour as an anxiety-driven reaction to what she experiences as a threat to her own status and the status of her children from their illegitimate but noble-born half brother. He prefers this interpretation to the idea that the conflict stems from jealousy between two women in a relationship with the same man.

Torfi generally considers the psychological motivations of saga characters in the context of the period in which they were written, focusing particularly on societal structures and the contradictions and tensions within them. He has been interested in the relationship between society and the human psyche and how it appears in literature, for example in the violent incident described above when two women literally came to blows.

"Most Icelandic sagas were written in the 13th and 14th centuries. This was a time of dramatic change for Icelandic society. The Commonwealth collapsed and Iceland became part of the Kingdom of Norway. This had significant consequences for individuals and families. Some people rose in social status while others fell. Changes like this generally cause anxiety for those who fear for their position in society. I wanted to look more closely at how that situation is reflected in the literature, even when narratives describe events that are far off in time and space from the authors and medieval audiences," says Torfi. image/Kristinn Ingvarsson

The relationship between society and literature

Ever since Torfi began his career as a researcher, he has been fascinated by the relationship between society and literature. He has often tried to look at literature in the context of the society from which it emerged.

"Most Icelandic sagas were written in the 13th and 14th centuries. This was a time of dramatic change for Icelandic society. The Commonwealth collapsed and Iceland became part of the Kingdom of Norway. This had significant consequences for individuals and families. Some people rose in social status while others fell. Changes like this generally cause anxiety for those who fear for their position in society. I wanted to look more closely at how that situation is reflected in the literature, even when narratives describe events that are far off in time and space from the authors and medieval audiences."

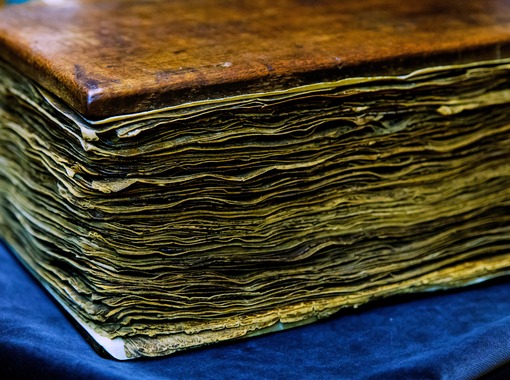

The Icelandic sagas are without a doubt the most remarkable contribution this little nation has ever made to world literature. Torfi has held many seminar and lecture on the sagas, mostly recently on this aspect of Laxdæla saga at the UI Humanities Conference and also at the International Saga Conference in Helsinki in 2022.

"I've also written a book chapter that presents a new interpretation of Laxdæla saga, exploring it in the context of the people and politics of the Age of the Sturlings. The Oddaverjar clan was related to the Norwegian royal family and this may have given them an advantageous position in the power struggle between the Icelandic chieftains. The paper is currently in peer review and hopefully will be published next year in a work about emotions in the Middle Ages. I have also created a database of the social status of the first settlers and other characters from the Icelandic sagas, with information on whether the person rose or fell in status after settling in Iceland. The goal is to continue research into the connection between violence and anxiety about social status in the sagas. I've already collected examples that suggest that this kind of anxiety is one of the main root causes of conflict in medieval society."

New methods – new knowledge

Torfi's methods represent a new approach to Laxdæla saga and he hopes that they will give us a more complete picture, not just of Laxdæla saga itself, but of the Icelandic sagas in general.

"My research will probably reveal new aspects of Icelandic medieval literature that scholars haven't previously explored. This will increase our understanding of these remarkable cultural treasures. It will also shed light on inequality-related anxiety and how this affects the experiences of individuals and wider culture."