Sometimes, just one little Christmas present can change your life. At any rate, that's what happened to Jón Emil Guðmundsson, lecturer in astrophysics at the University of Iceland. When he was a little boy, ripping the glossy paper off a Christmas present from his parents, he had no idea how much the book he'd just unwrapped would influence the course of his life. The book was The First Three Minutes by Steven Weinberg, subtitled: A modern view of the origin of the universe. Shortly afterwards, Jón Emil received illustrated editions of the books of Stephen Hawking, the English theoretical physicist and cosmologist. There was no turning back. But what is cosmology? It is the branch of astrology and astrophysics that focuses on the universe, its history and its future.

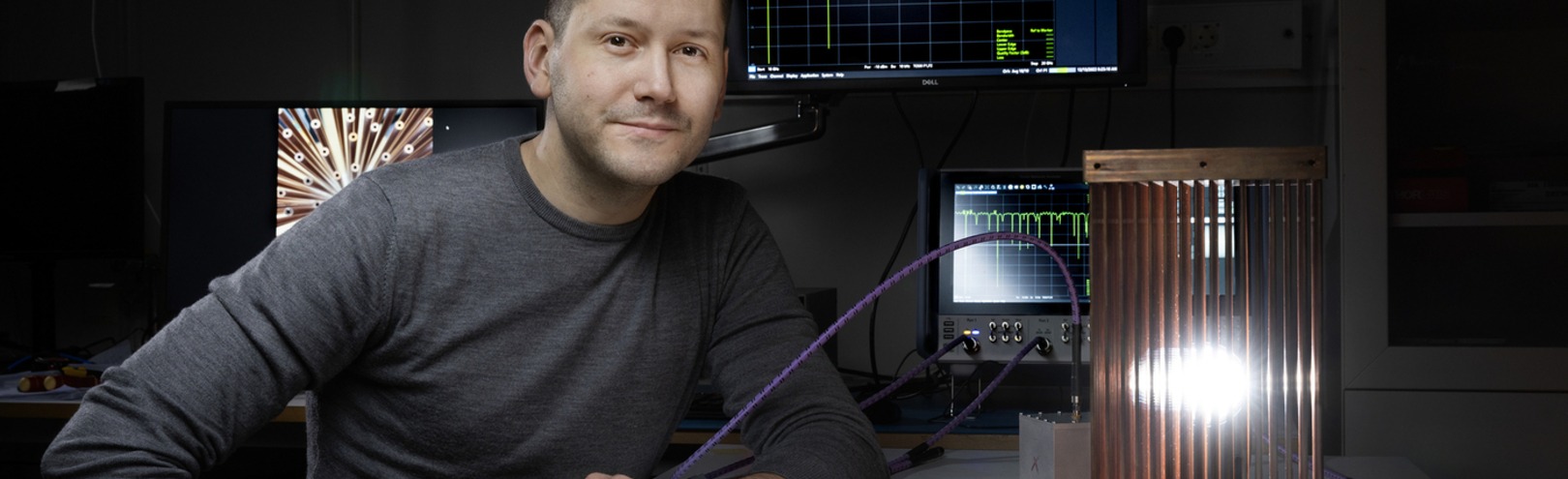

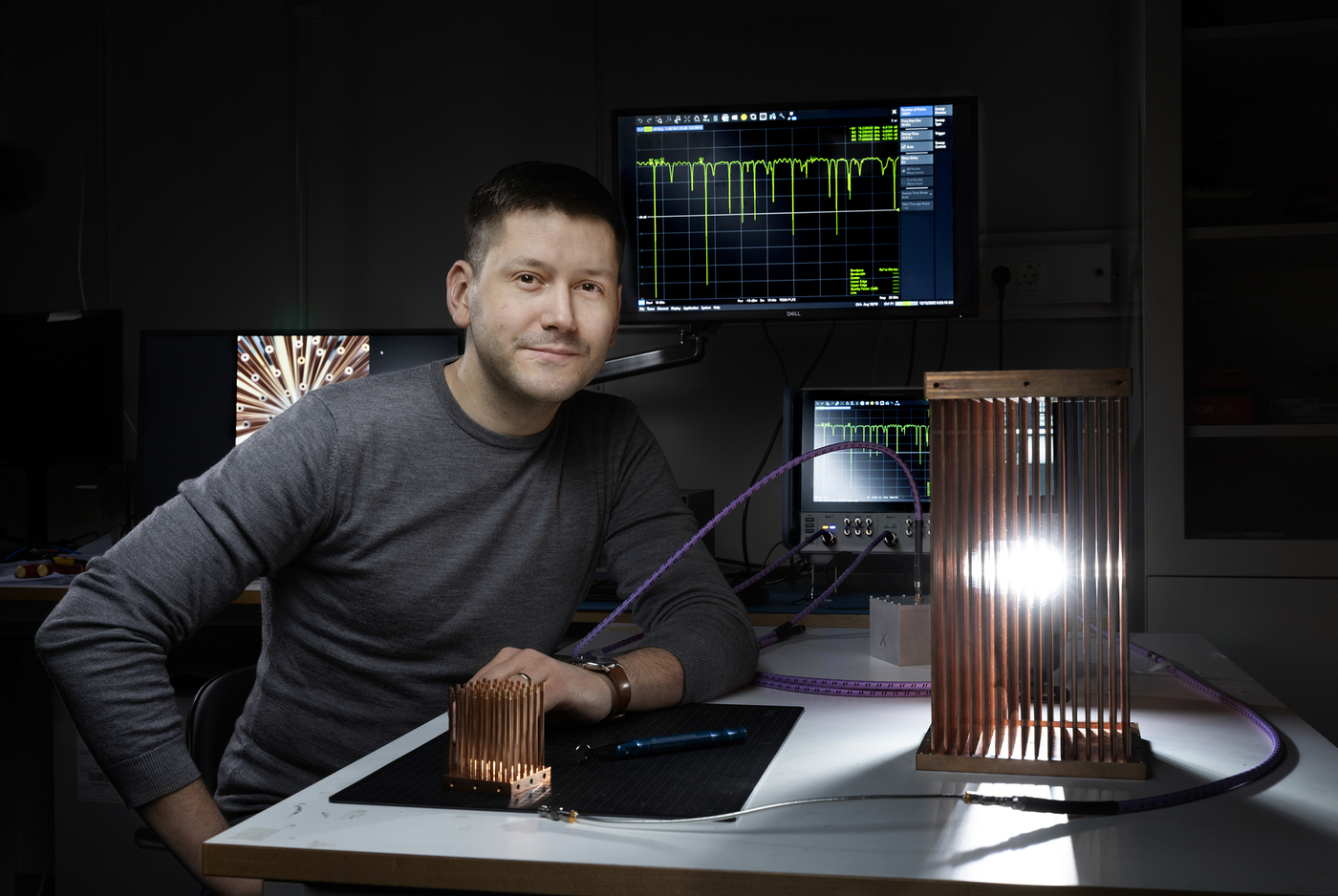

Jón Emil was born in 1985 and completed his long education in 2014 with a PhD in astrophysics from Princeton University, one of the most prestigious universities in the world. Although this was the end of his formal education, Jón Emil's pursuit of new knowledge has continued unabated and he is now one of Iceland's leading astrophysicists.

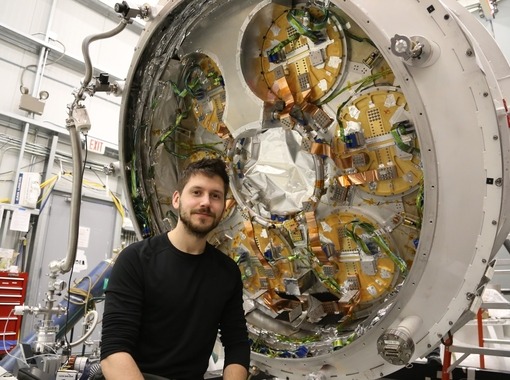

"My research is mainly about the cosmic microwave background, i.e. the oldest light in the universe, and what this light can tell us about the history and properties of the universe. Recently I have been concentrating on the design and calibration of the microwave telescopes which will be used for this research over the next years," says Jón Emil, who is a prolific researcher in this field. He is referring here, for example, to Taurus, NASA's balloon-borne telescope mission, the Simons Observatory telescopes in the Atacama Desert in Chile, and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's LiteBIRD satellite which will be launched later this decade.

"We strive to understand the properties of the telescopes as well as we can, so that we can understand the data they produce. These telescopes are designed to search for something that's like a needle in a haystack, so we need to be very familiar with them and how they work, e.g. their limitations, in order for that search to be successful."

Jón Emil Guðmundsson talks about his research

Invisibility helmets, metamaterials and Guardians of the Galaxy

People have always been fascinated by the stars, and topics like human space travel and extraterrestrial beings have long captured people's imaginations in science fiction.

Jón Emil doesn't exactly have science fiction in mind as he searches for new knowledge in the fields of physics, engineering and astrophysics. Strangely, though, one of the aspects of his research is the possibility of making people and objects invisible, not too dissimilar to what we we see in Guardians of the Galaxy.

Jón Emil explains: "I am working with so-called metamaterials, which have interesting effects on microwaves and which can be used in various ways, e.g. in the design of invisibility helmets, antennae and cameras that seem to almost break the laws of physics." He adds that it's not such a big leap to projects related to quantum computers and communication devices of the future, 5G and 6G.

Jón Emil is actually of the opinion that art and science overlap a lot more than people think. "There are so many similarities between artistic creation and scientific research," he says. "For example, a lot of scientific work is very creative, but that side of it tends to get lost when we present our main findings. I think that both science and art can inspire us and spur us on to great achievements. They both help us to understand ourselves, our society and the world we live in."

"We strive to understand the properties of the telescopes as well as we can, so that we can understand the data they produce. These telescopes are designed to search for something that's like a needle in a haystack, so we need to be very familiar with them and how they work, e.g. their limitations, in order for that search to be successful," says Jón Emil Guðmundsson.

Coincidences and a chain reaction of discoveries

Jón Emil says that one discovery often leads to others. Numerous technological innovations have been developed alongside basic research in physics.

"The cosmic microwave background, for example, was discovered quite by chance by scientists at Bell Labs in New Jersey in 1965. Around that time, scientists at the same institute were inventing the technology behind modern microprocessors and establishing the mathematical and electrical engineering principles behind modern telecommunications networks. By that I mean things like mobile phones and wireless network connections. At that time, this was all basic research, but the applications of that research are now ubiquitous in our society."

This is a typical example of how research into a single or few topics can lead to a whole range of inventions in many different areas.

Wide-ranging research in the field of astrophysics

Jón Emil's research interests span a wide range and not just because his sights are set on outer space. "I particularly enjoy the aspects of experimental physics that enable us to follow a project from beginning to end," he says. "For example, in astrophysics we have the opportunity to control the basic design of a telescope; then move on to production and be actively involved in various difficult decisions to do with optimisation; then set up the telescope and make sure everything is working properly – sometimes this work takes place in incredible locations such as the Atacama Desert in Chile; then come home with the data, design methods to process the data, and finally, hopefully, celebrate when those measurements help us to understand the universe."

This is clearly a huge undertaking.

Jón Emil thinks a little before talking about the most significant findings from his research:

"I suppose the findings from the Planck satellite have had the most impact. Planck is an ESA satellite launched in 2009, which has provided evidence to support our basic ideas about cosmology and the significant role of dark energy and dark matter in the the history of the universe. In recent years, my most important findings have been to do with the design of the Simons Observatory telescopes, which will begin taking measurements in the Atacama Desert later this year."

Many things we now take for granted were once the topics of research

It was Jónas Hallgrímsson, the beloved Icelandic poet, who translated the first astronomy textbook into Icelandic. The book, which was published in 1842, was entitled Stjörnufræði, létt og handa alþýðu in Jónas' translation (Basic astronomy for a general audience). The original author was the Dane G.F. Ursin.

The translated book contains a plethora of neologisms coined by Jónas that have now become established in everyday Icelandic, such as the Icelandic words for planet, gravity, halo, rotation speed and telescope – the last of which is the most important piece of equipment in Jón Emil's research.

When Icelanders look up at a clear and starry night sky, they may think of the words Jónas introduced to the language without knowing where they came from.

But perhaps what we all feel first and foremost, regardless of language, is a sense of the beauty of the universe. But why is it important to research things like the first light, the stars, space and the universe?

"There are so many different ways to answer that question," says Jón Emil. "Why does it matter to know that the Earth orbits the sun rather than the other way round? Why does it matter to know that many of the elements necessary for life on our planet were created inside stars that died long ago? Why does it matter whether we understand the laws of physics that describe the first fractions of a second in the history of the universe? Maybe none of it matters when you get down to it, but it's fascinating nevertheless. Things that we take for granted now were once the topics of scientific research."

Last autumn saw the start of the CMBean project at UI, which was awarded an ERC grant from the European Union of around ISK 300 million. Jón Emil is leading this project. "We are using the EU funding to establish a sophisticated laboratory at UI which will be used to design the microwave telescopes of the future: telescopes that will enable us to learn more about the history of the universe. The lab also houses technical equipment that will open up whole new horizons for teaching in experimental physics, electrodynamics and even mechanical engineering," says Jón Emil.