"Grettir said that his temperament had not improved and that he had much more trouble restraining himself and was much quicker to take offence than before. He noticed a marked difference in that he had grown so afraid of the dark that he did not dare to go anywhere alone after nightfall – he thought he could see all kinds of phantoms."

This is a quotation from The Saga of Grettir the Strong, describing how the protagonist is tormented by darkness. The reader sees clearly how anxiety, fear and hallucinations haunt Grettir Ásmundarson, a man with the physical strength to take on almost anything, except the dark.

Anyone who reads will have noticed that darkness can play a significant role in staging and narrative, but also that it has symbolic significance in literature and language. For example, this description of the interplay between the opposites of dark and light uses poetic imagery that could almost be taken from modern literature.

"Like the dark mists that are drawn up out of the ocean, dispersing slowly to sunshine and gentle weather, so did these verses draw all reserve and darkness from Þórdís’ mind and Þormóður was once again bathed in all the brightness of her warm and gentle love."

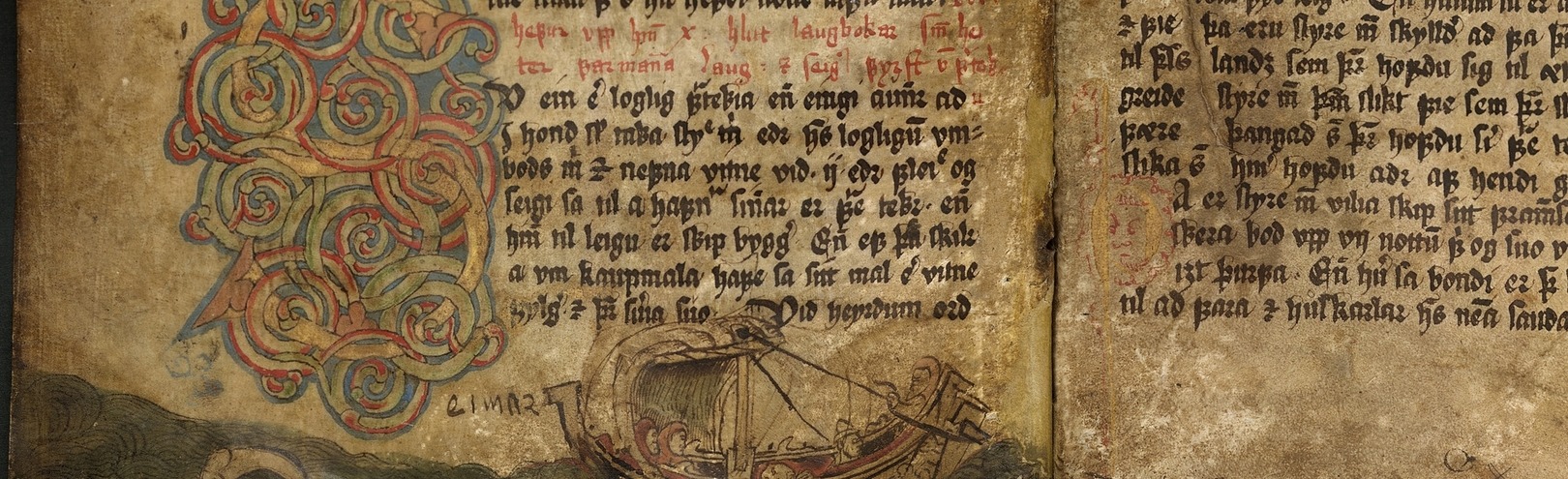

Exploring the darkness in Njál's Saga, Egil's Saga, Laxdæla Saga and other Icelandic sagas

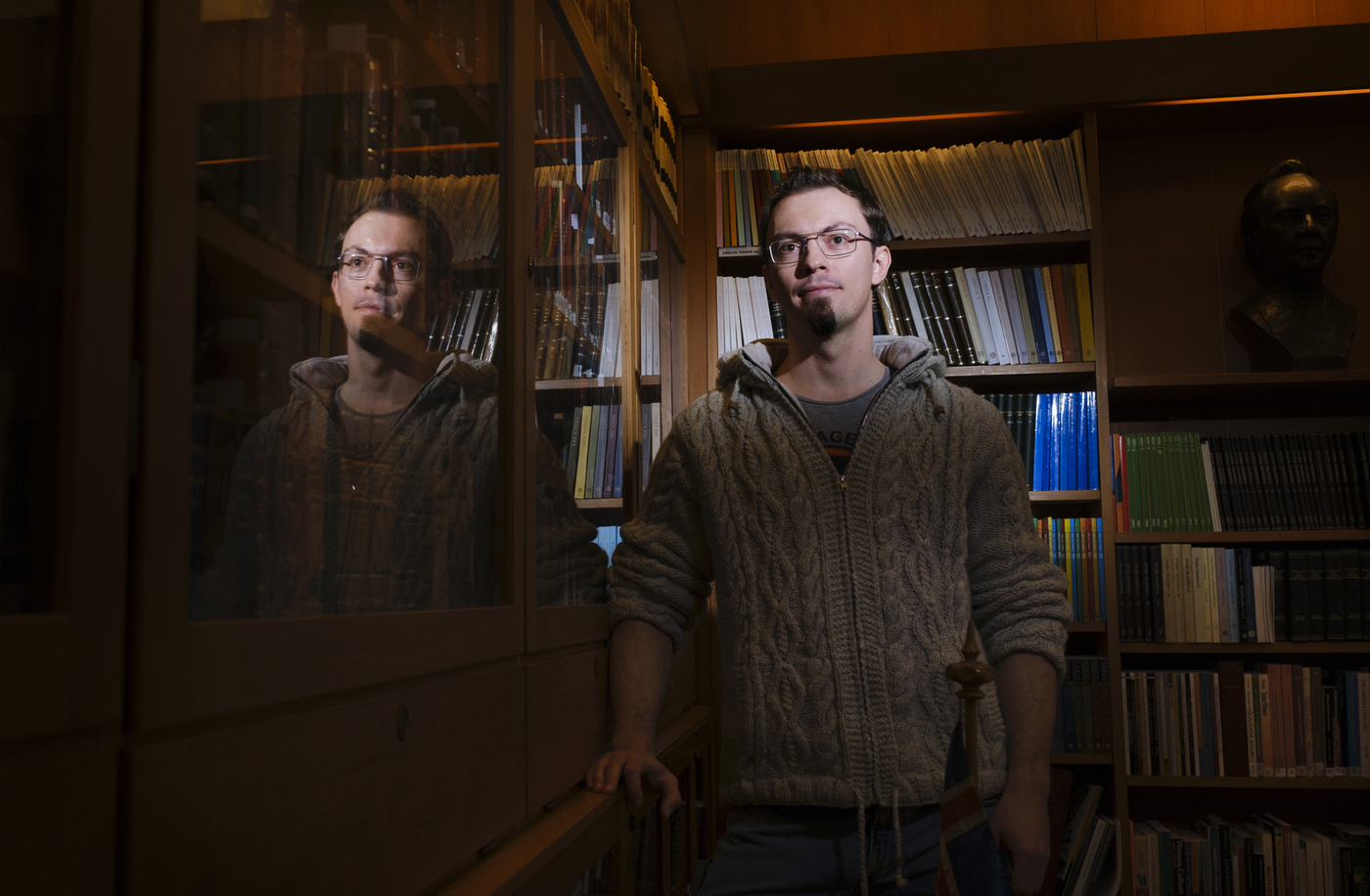

All this darkness in the Icelandic sagas is now the subject of a research project at the University of Iceland by Jan Alexander van Nahl, senior lecturer in medieval Iceland studies.

"I didn't grow up in Iceland, so perhaps the dark of the Icelandic winter is particularly striking for me," says Jan Alexander, who also noticed the darkness in the Icelandic sagas, which he has been reading for a long time both for pleasure and scholarship.

Jan Alexander was born in Bonn in Germany, but since emigrating to Iceland has become proficient in the Icelandic language. He has spent many years exploring the role of medieval studies in contemporary society, having absorbed himself in the Prose Edda. The Prose Edda is the masterpiece of Snorri Sturluson, one of the Sturlung clan and a man who lived through a period of enormous unrest in Iceland in the 13th century. The significance of Snorri's Edda cannot be overstated, since it is the most valuable surviving source of Norse mythology.

Jan Alexander has published two books about Snorri and a book about the Kings' sagas. He has also written a book about digital humanities, a textbook on Norse medieval studies, and a book about Iceland and the Icelandic language for German tourists.

Jan Alexander van Nahl, senior lecturer in medieval Iceland studies

One of the first scholars to explore the darkness

Jan Alexander explains that darkness is a pretty important part of our natural lives. Very few people now have to fumble about in complete darkness, though, unless there is a power cut, an increasingly rare occurrence considering all the technology we now take for granted.

"Few medievalists have turned their attention to darkness so far, despite the fact that it has always been so striking in literary texts, especially Icelandic texts, ever since the middle ages. I find it fascinating, for example, that there was no street lighting in Iceland until the second half of the 19th century, several hundred years later than most places in mainland Europe."

Jan Alexander says that people in European cities attempted to banish the darkness over 400 years before such action was taken in Iceland. The advent of electric lighting in both urban and rural areas significantly improved people's quality of life, but once the light had penetrated the shadows, it was as though people began to miss the dark. We now often talk about light pollution, which was previously a completely unknown concept, when we want a clearer view of those things that disappear as the light touches them.

"I have wondered whether Icelanders were more accustomed to the darkness than mainland Europeans, or more conscious of it. At least I find darkness a tremendously exciting challenge," says Jan Alexander, adding that his research project is focused on discovering the role of darkness in the Icelandic sagas and defining its significance in medieval society.

Darkness liberates and destroys

"The Icelandic sagas often refer to darkness as a natural thing that can be useful for a time, but nevertheless something that people have no control over. Darkness can destroy characters physically, but also mentally, as we see in The Saga of Grettir the Strong," says Jan Alexander.

"Egil's Saga contains several good examples of events where the darkness plays a key role. For example, it tells of a man who attacks his enemies in a sleeping chamber in the middle of the night, but is then slain himself right after sunset in front of his own house. The darkness has little relevance to the character's mental state, but we see how it provides an opportunity to a killer, but also causes his downfall – the darkness sets the rules. Darkness is presented as a temporary state that allows someone to get away with murder, possibly multiple murders, but even in that moment of success there is a certain tightrope walk between victory and defeat. Killing a man in the dark is nevertheless a dark act, as most people would have seen it when the sagas were being written."

Jan Alexander explains that the protagonist of the saga, Egill himself, is saved from swift execution in the middle of the night when his friend Arinbjörn argues that "night-slaying is murder".

Aribjörn's words persuade Queen Gunnhildur to delay Egill's execution. And the shadows continue to protect Egill, as under the cover of darkness he uses the reprieve to compose a poem praising King Eiríkur Bloodaxe, a poem which ultimately saves his life. "Darkness is therefore a theme that connects cunning, death and salvation in Egil's Saga."

"Egil's Saga contains several good examples of events where the darkness plays a key role. For example, it tells of a man who attacks his enemies in a sleeping chamber in the middle of the night, but is then slain himself right after sunset in front of his own house. The darkness has little relevance to the character's mental state, but we see how it provides an opportunity to a killer, but also causes his downfall – the darkness sets the rules. Darkness is presented as a temporary state that allows someone to get away with murder, possibly multiple murders, but even in that moment of success there is a certain tightrope walk between victory and defeat." A drawing of Egill Skallagrímsson.

Darkness woven into emotional states

Jan Alexander explains that references to darkness in the great literary tradition of the sagas are diverse, complex and occasionally elude us somehow if we try to pin them down. He believes that although his research attempts to explore the role of darkness in a literary sense, it is often woven somehow into the emotional state of the characters, as indeed occurs in our own contemporary reality.

"Now I will show that my character is not dark. Njáll has asked me for help, and I have agreed to it, and given my word to aid him. He has often given me and many others the worth of it in cunning counsel."

So says Hjalti Skeggjason in Njál's Saga. The reader gets an insight into Hjalti's thoughts through the visual power of his language.

Jan Alexander reports that reading the Icelandic sagas with a focus on darkness provides insight and understanding of the mental state of people during the so-called 'dark ages' and can even provide a fresh perspective in the ongoing exploration of mental health today.

"I believe that a better understanding of people's mentality in the medieval period can also tell us something about our own mentality today – on the whole, people then were no different to people now, and darkness is a significant phenomenon to this day."

Although Jan Alexander has previous given lectures and published books on the shadows within the Icelandic sagas, he says that he has not yet exhausted the topic. He has now been awarded a two-year research grant to delve deeper into the darkness in Iceland's literary heritage.

"I have not yet come to any significant conclusions, but it is clear that broader research will yield a better insight into the mentality in Iceland in the medieval period."

Enigmatic and complex texts

Jan Alexander grew up in rural Germany and says that his affinity with Norse literature was probably first sparked by his mother, who was an expert in Germanic linguistics. He had travelled to Iceland as a tourist before he started working here and was also an exchange student in Uppsala just over 15 years ago, when he took several courses on Eddic poetry and the Prose Edda.

"I was immediately taken with these enigmatic and complex texts and I decided to explore them in greater detail. As soon as you start delving into these texts, you are constantly making new discoveries and learning more about humanity that is universal, although these are ancient texts."

Jan Alexander says that he always tries to identify links between the Icelandic sagas and other European medieval literature, "but actually, these long prose texts about medieval society here in Iceland are unique in many ways. The Icelandic sagas are so much more than conventional heroic epics. You can read them again and again and find something completely new each time, no matter how learned you are in this field or how much other people have written about them."

The advance of humanities at UI

The new Strategy of the University of Iceland identifies trust as one of the guiding principles, with a focus on attracting staff from diverse backgrounds. It is vital for universities to bring in people who can share their experiences from other countries. Jan Alexander is certainly one such person, with a Master's degree from the University of Bonn in Scandinavian studies, cultural geography and archaeology. He also has a doctorate in Scandinavian studies and archaeology, as well as a Habilitation degree in Scandinavian studies, both from the University of Munich.

"I find the University of Iceland a progressive and solution-orientated institution that gives staff and students the freedom to find their own paths in research, teaching and learning, while focusing everyone in a certain direction when necessary. This fosters diversity," says Jan Alexander.

"In some countries the humanities are struggling, not least medieval studies, since the focus has been redirected towards hard science. The humanities are largely a social discipline and they are thriving at the University of Iceland – I love being part of this."