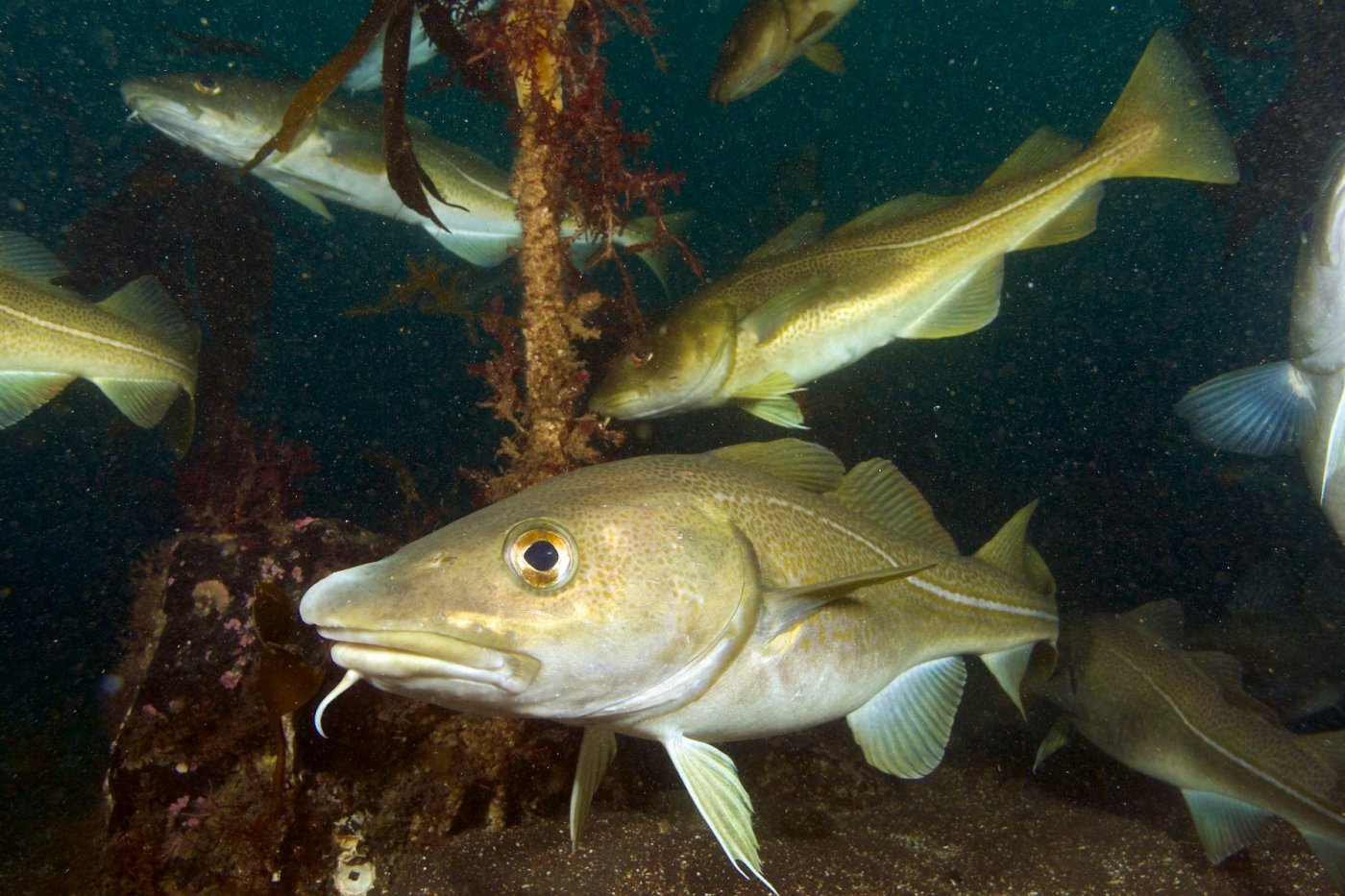

An international team of scientists, including researchers from the University of Iceland, has developed a new method for finding genes related to the natural selection of species. The method has been used, for example, to shed new light on natural selection in the Icelandic cod stocks and cod in the Barents Sea.

As many people know, the naturalist Charles Darwin proposed the theory of natural selection around 160 years ago. In brief, the theory of natural selection is based on the idea that gene mutations which make individuals within a certain species better able to survive in a certain environment will be replicated between generations at a greater rate than others. Competition is fierce between individuals of the same species and between different species. This leads to natural selection, which is the explanation for the diversity of living organisms and their adaptation to different environments.

One of the main objectives of scientists in the field of population genomics has been to understand how this adaptation of organisms to localised environments affects the pattern of genetic variation in the genome and find ways to analyse this pattern. Among those who have been working on this extensive project are Einar Árnason, professor of evolutionary biology and population genetics at the University of Iceland Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences, and Katrín Halldórsdóttir, research specialist at the Institute of Life and Environmental Sciences. They have focused in particular on natural selection in the most major commercial fish in Iceland, the cod.

"The main conclusion of our research is that genes for important adaptations to the environment, including in the immune system and metabolic pathways, can be found in various little researched human populations. We also found genes for muscle mass, milk production and tameness in certain bovine breeds. The research also showed in which populations a large area of the codfish genome underwent natural selection. The research therefore showed that chromosomal inversion, where part of the chromosome breaks in two places and flips around, meant that large parts of the habitat types 'deep water fish' and 'shallow water fish' were naturally selected and increased in frequency in the Icelandic cod population and the cod population in the Barents Sea," says Einar Árnason, pictured here with Katrín Halldórsdóttir.

In recent years, Einar and Katrín and their colleagues at Danish universities have been working on the research discussed in an article newly published in the scientific journal Genome Research. The research objective was to develop a new method to detect and evaluate natural selection in complex population histories. The method, which they have named 'Graph-aware Retrieval of Selective Sweeps', has proved extremely effective for detecting genes in the genome that have been strongly selected. The method can also identify which branch of the family tree was affected by natural selection.

The scientists involved in the research further developed the method and tested it on data from various populations: human, specific bovine breeds and Atlantic codfish.

"The main conclusion of our research is that genes for important adaptations to the environment, including in the immune system and metabolic pathways, can be found in various little researched human populations. We also found genes for muscle mass, milk production and tameness in certain bovine breeds. The research also showed in which populations large regions of the codfish genome underwent natural selection. The research therefore showed that chromosomal inversion, where part of the chromosome breaks in two places and flips around, meant that large parts of the habitat types 'deep water fish' and 'shallow water fish' were naturally selected and increased in frequency in the Icelandic cod population and the cod population in the Barents Sea," says Einar.

Einar and Katrín also point out that the results underline the importance of understanding the genomes of these two cod habitat types that may have have contributed differently to the fishing stocks used by Icelanders. "It is also important to use this method to further investigate various other genes that could be identified and which demonstrate adaptation to various localised conditions. The research is socially significant in terms of the basic understanding, protection and management of an important fishing resource," adds Katrín.

This research was part of a larger project by Einar and Katrín entitled "Population genomics in high-fecundity cod", which received a three-year excellence grant from the Icelandic Research Fund last year.