Robust scientific research is based on collaboration between scientists, with students, across national borders and even across disciplines. In recent years, strong research teams have been developed at the University of Iceland exploring a wide range of subjects under the leadership of outstanding scientists. Among them is Hans Tómas Björnsson, professor at the Faculty of Medicine, who is working with his research team in Iceland and Baltimore, USA, to explore whether it is possible to treat intellectual disabilities caused by a rare genetic disease called Kabuki syndrome. Hans Tómas is also the only scientist at the University who has had a syndrome named after him and received yesterday the biggest scientific recognition awarded in Iceland.

Hans Tómas began working at the University of Iceland in 2018 after a decade at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he had completed his PhD in human genetics in 2007. He also completed specialist training in paediatric medicine and clinical genetics there and his research interests have been in these areas, with particular emphasis on epigenetics. Epigenetics is the study of changes to DNA or histone proteins which affect how tightly they are packed in the chromatin and therefore gene expression. Hans Tómas is an associate professor at Johns Hopkins alongside his position as professor at the Faculty of Medicine and senior consultant in clinical genetics at Landspítali University Hospital.

Subtitles available under settings

Three diagnosed cases of Kabuki syndrome in Iceland, but probably many more

Hans Tómas and his colleagues in the Björnsson research team have directed their focus on Kabuki syndrome, a rare genetic disease that causes intellectual disabilities, growth deficiency and immunodeficiency. The disease was first described around 40 years ago. "The prevalence of the disease is believed to be 1 in 30,000; but there are certainly others who are not diagnosed. In Iceland, we have diagnosed three individuals with the syndrome but there are probably others who are undiagnosed," says Hans Tómas.

His interest in the syndrome was aroused during his PhD. "As a PhD student, I was working on research in epigenetics and found it incredible how much variety we saw in epigenetic marks in healthy individuals. The idea occurred to me that we could influence epigenetics in order to treat diseases," he says.

Hans Tómas is an associate professor at Johns Hopkins alongside his position as professor at the Faculty of Medicine and senior consultant in clinical genetics at Landspítali University Hospital. image/Kristinn Ingvarsson

Challenging accepted ideas about intellectual disability

Just over 10 years ago, scientists discovered the so-called Kabuki genes, i.e. the genes that mutate to cause Kabuki syndrome. They are called KMT2D and KDM6A and since that time, the former has been the research focus of Hans Tómas and his colleagues. "Genes control the opening of the chromatin; at many points in the genome the chromatin is too tightly packed to allow genes to be expressed and I wanted to experiment with whether it would be possible to treat some of the symptoms of the syndrome using drugs that affect epigenetics and help to open the chromatin," he says, speaking of the inspiration behind the research.

Hans Tómas points out that the received wisdom on intellectual disabilities tells us it is not possible to treat them after birth. The team's research and other work, however, suggests that this is not the case, at least with regard to Kabuki syndrome.

"Our research indicates that mutation of the KMT2D gene causes disruptions to a process called neurogenesis. This is an active process that continues long after birth and can therefore be influenced. These neurons behave abnormally and there are fewer such neurons in mice with Kabuki syndrome than in healthy mice, according to our research. We have been able to increase the number of such cells using drugs that affect epigenetic marks," explains Hans Tómas.

"We have also demonstrated that patients with Kabuki syndrome have an impaired ability to distinguish between different patterns; this supports the idea that the disease is linked to the part of the brain where neurogenesis takes place. We have also discovered other things associated with Kabuki syndrome, such as abnormal development of the so-called Peyer's patches in the intestine, which actually control the immune response in the intestinal tract. Our research shows that the patches are smaller and much fewer in mice with Kabuki syndrome than in healthy mice. We believe this could explain why individuals with Kabuki syndrome often suffer serious food allergies early in life," he adds.

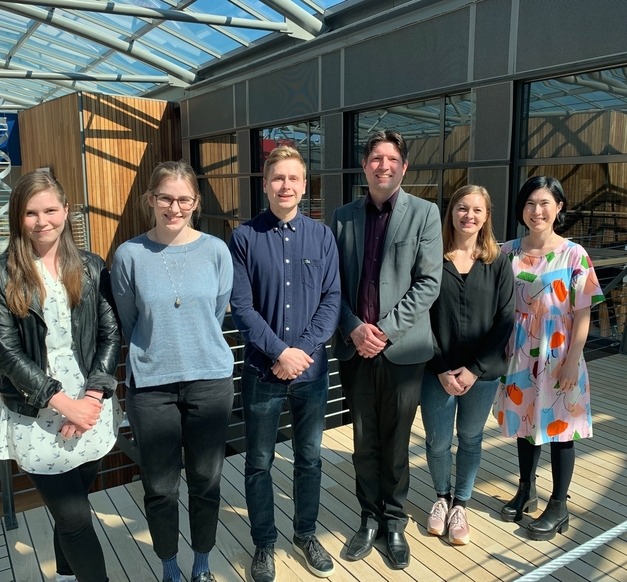

Hans Tómas with his research team at the University of Iceland Biomedical Centre in the deCODE genetics building. His lab team includes a lab director, five PhD students and one Master's student. "In Baltimore, the Björnsson lab employs a lab director, two post-docs and one PhD student. I also have a large number of collaborating partners and a particularly large network outside Iceland," he adds.

Syndrome named after Hans Tómas

Hans Tómas has established himself with his research team at the University of Iceland Biomedical Centre in the deCODE genetics building. His lab team includes a lab director, five PhD students and one Master's student. "In Baltimore, the Björnsson lab employs a lab director, two post-docs and one PhD student. I also have a large number of collaborating partners and a particularly large network outside Iceland," he adds.

The team's research is not exclusively focused on Kabuki syndrome. They also look at various other syndromes related to disorders of the epigenetic machinery. One such syndrome is a new genetic disease that Hans Tómas and his colleagues first described in 2017, which has been named Pilarowski-Bjornsson syndrome after Hans Tómas and his former PhD student Genay Pilarowski, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. The syndrome causes intellectual disability, often with autistic features, and speech disorders.

The research team has received grants from both Icelandic and international research funds and Hans Tómas was recently awarded an excellence grant from the Icelandic Centre for Research. Asked about their plans for the future, Hans Tómas says that the team is interested in better understanding the relationship between mutations in the aforementioned KMT2D gene and the characteristics of Kabuki syndrome. "I am now supervising two PhD students, Sara Þöll Halldórsdóttir and Hilmar Gunnlaugsson Nielsen, who are trying to get a better understanding of why the disease affects both bones and neurons," he says.

Hans Tómas says that the significance of the team's research is that, along with other research, it suggests that it might be possible to treat more kinds of intellectual disability postnatally than had previously been believed. "People have been very hesitant to work in this area because most people have hitherto believed that the damage is already done at birth. Intellectual disability affects a large proportion of children and it is costly for society and families to deal with the consequences. For this reason, it is important to get a better understanding of the processes behind it and develop the best possible treatments," he concludes.