At the moment, most people probably connect the idea of a prediction model with news about the infection rate in the coronavirus pandemic. One of those working on creating that prediction model is Brynjólfur Gauti Jónsson. This year he completed an MS in statistics from the University of Iceland and is currently doing a PhD in biostatistics.

For his Master's thesis, Brynjólfur researched the methodology behind predictive modelling for age-related mortality rates. This kind of prediction model is used a lot in actuarial science, for example when pension funds calculate people's expected lifespans.

These statistics are used by pension funds to determine how high monthly pension payments should be. The more accurate the prediction models, the more likely it is that pensioners will receive all the money in their funds. Models also reduce risk for the pension fund.

Based on an old classic

Brynjólfur's research is based on developing an old, familiar prediction model. "This model is nothing new," says Brynjólfur, "The Lee-Carter model dates from the early 1990s; it's actually an old classic. What we were doing was adding criteria about close age groups being more similar than distant age groups," says Brynjólfur, referring to the research conducted by him and his supervisor, Birgir Hrafnkelsson, professor of statistics at the Faculty of Physical Sciences. According to Brynjólfur, his supervisor has done a lot of work in spatial statistics, which Brynjólfur used in his own research.

"Birgir works a lot with meteorological data. If you have lots of weather stations, not all the stations will have independent measurements. If they are very close to each other, the measurements are quite similar. I took these ideas from spatial statistics and thought that if age was like distance, then we could make the model find some link between age groups so that greater distance meant less similarity. It was quite surprising how well it worked for the model," he explains.

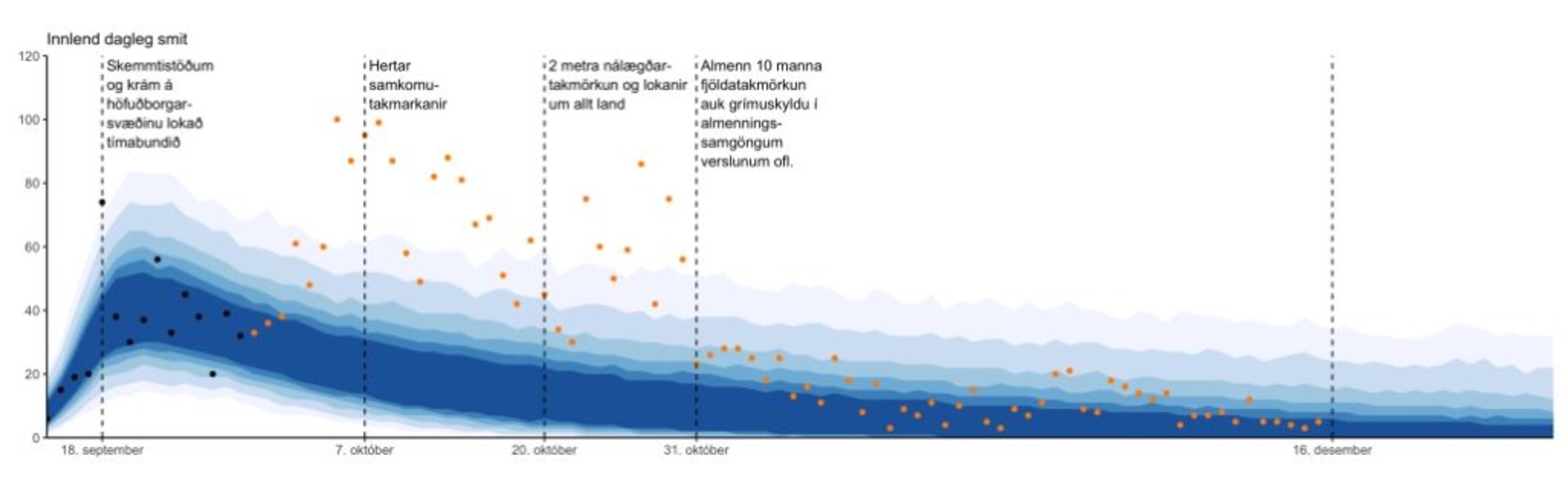

It is not unprecedented to take a prediction model from one field and apply it in another. For example, the COVID-19 prediction model originally comes from ecology. "In ecology, there is a lot of research into models that predict things that have a maximum value. Like plants, they grow and reach a certain size. Animals also reach a certain size. It's an ecological model for things that have a maximum limit that was then applied to the number of infections in the COVID-19 pandemic, which also has a maximum limit," says Brynjólfur Gauti Jónsson. image/kristinn ingvarsson

Ecology and infectious diseases

It is not unprecedented to take a prediction model from one field and apply it in another. For example, the same is true of the COVID-19 prediction model. It originally comes from ecology. "In ecology, there is a lot of research into models that predict things that have a maximum value. Like plants, they grow and reach a certain size. Animals also reach a certain size. It's an ecological model for things that have a maximum limit that was then applied to the number of infections in the COVID-19 pandemic, which also has a maximum limit."

In his PhD, Brynjólfur intends to look more closely at the link between ecological prediction models and infectious disease prediction models.

"They both work well, it seems. And this is linked to my Master's thesis because there I was also working with a tiered modelling approach. Instead of giving every individual age group some parameters with no consideration of what is happening in the other age groups, I wrote the model such that it learns from close age groups. It was exactly the same with the COVID-19 model – instead of evaluating every country individually, it uses a comprehensive global evaluation and the model learns from that," he said.

Brynjólfur points out that statistical prediction models are very successful as long as conditions do not change quickly. "Because it is always based on existing data. If you get completely different data in the future, the models don't work anymore, or if there are some unforeseeable circumstances that the models can't predict. Some examples of that would be mass infections in the coronavirus pandemic or the impact of a civil war on mortality prediction models. Then you will get some inaccurate results. But statistics as a discipline is about being wrong, just not systematically," he jokes.

A statistics book that everyone should read

Brynjólfur is so passionate about statistics that he reads a lot about the subject beyond his course material. He says he has adopted the reading practices of the statistician Nassim Nicolas Taleb. "I read a book until I can't be bothered with it anymore or I don't understand it. Then I just read another book. I might return to the first book later. That way I always enjoy reading."

One of the books that Brynjólfur has read and which strongly influenced him is Statistical Rethinking by Richard McElreath. This is the book that Brynjólfur has recommended to as many people as possible and endorsed wherever he can, for example in his Master's defence.

"It's the best statistics textbook I know and I think most people should read it. It was actually also the inspiration for my research into age-related mortality rates. The book says that you can't always have some null hypothesis and reject it. You have to create some model that has a chance of explaining the world. Then you have to see how it gets things wrong. Then you make another model and compare them, how they get things wrong. And that's how you learn," he concludes.

Author of the article: Halldór Marteinsson, student in Public Administration, MPA.