Árni Magnússon (1633-1730) is an important figure in Icelandic history. His influence is still felt today, and it is thanks to him that Giulia Zorzan, doctoral student of history at the University of Iceland, has access to the materials she needs to work on her research.

Árni Magnússon was a collector of manuscripts, and was instrumental in saving many of them from being lost. From an early age he had a passion for ancient lore – just like Giulia - and eagerly started collecting manuscripts on his travels around Iceland. Árni resided in Copenhagen for most of his life, and by the start of the eighteenth century he had acquired the most impressive collection of Icelandic and Norwegian manuscripts in the world.

When it comes to ancient manuscripts there are many avenues open to curious researchers. Many scholars are thus interested in the content of the manuscripts; the stories told on their pages. Other scientists are fascinated by the social conditions at the time of their production, and about the scribes and their societal standing. Finally, there are those who are interested in the age of the manuscripts, and technical details, such as the substances and pigments used for writing: the ink.

Studies the ink in the manuscripts

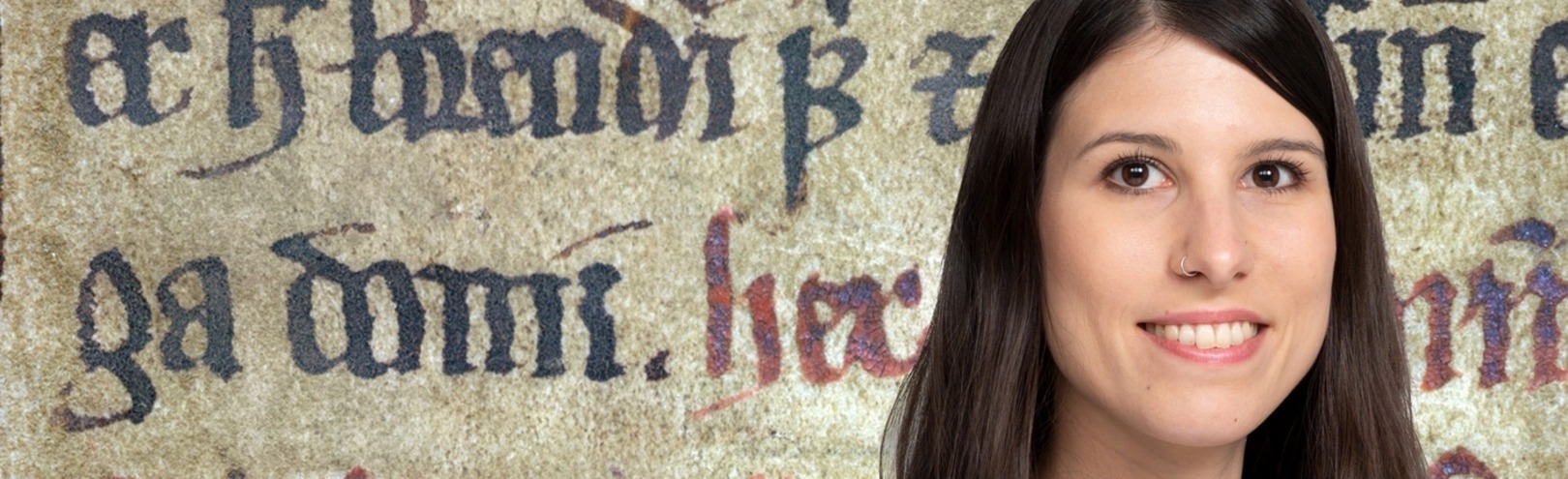

This is precisely the focus that Giulia Zorzan has chosen for her research, the ink and the pigments used in it. She is studying the oldest Icelandic manuscripts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

She examines how different colours play roles in the formatting of each page. It seems incredible that it is still possible to read and scrutinise text written eight hundred years ago, and even more amazing that colour differences can easily be discerned with the bare eye. Giulia’s hypothesis is that you can use these colours as a kind of key to the text itself. She also analyses the quality of the pigments used in the first period of Icelandic manuscript creation.

“I mostly work with red, green, blue and yellow in titles, first letters and other philological elements,” says Giulia.

“The project is still in its opening phases and analysing the pigments is planned over the next few years. The first results indicate that scribes started using colouring at very early stages in manuscripts here. By analysing how different colours repeat on pages it is possible to better understand how the pigments were developed and how they serve a purpose as part of the whole manuscript.”

“I mostly work with red, green, blue and yellow in titles, first letters and other philological elements,” says Giulia. By analysing how different colours repeat on pages it is possible to better understand how the pigments were developed and how they serve a purpose as part of the whole manuscript.”

Understanding the beginning and development of writing culture in Iceland

The manuscripts have for the past few decades been stored in Árnagarður, but soon they will be moved to a new home in the house for Icelandic studies, that will formally open later this year.

Giulia studies ink and text in the manuscripts to gain basic information on the pigments in Icelandic manuscripts. This is new data on a basic element of the first phase of Icelandic literary culture. She says that the study will help to better understand how written culture developed in Iceland and to get a sense of the premises that led to writing flourishing here during the middle ages.

“In my former projects I have studied the oldest Icelandic manuscripts extensively mainly focusing on the spelling. In this project I decided to expand my horizon and experiment with a new approach that will hopefully inspire further research in this field.”

Giulia says that on the whole the study provides an opportunity to know more about the beginning of writing in Iceland and the unique heritage the manuscripts represent for Icelandic society, while at the same time “giving an opportunity to understand the cultural and social context that gave birth to the manuscripts.”

Giulia says that the importance of research on these special factors in the complex nature of the Icelandic manuscript will help us to understand the origins of materials and the professional knowledge in place in the scriptoria in Iceland where the manuscripts were produced. The relationship between scribes in Iceland and on the continent can also be better mapped using this approach.

Giulia’s supervisors are Beeke Stegmann, manuscript specialist and research lecturer at the Árni Magnússon Institute, and Már Jónsson, professor of history at the University of Iceland.

Born in Italy and studied manuscripts in Milan

Giulia is born in Italy and holds an MA in Nordic Philology from Milan University. Her interest in Icelandic culture and manuscripts was kindled when she was on an exchange at Lund University in Sweden. There she took a course in old Icelandic and literature as part of basic Scandinavian studies.

“In my MA studies in Milan I became interested in studying manuscripts, first and foremost focusing on the Latin tradition, and then I decided to combine this interest with my studies on Nordic culture. This led to my moving to Iceland to continue my academic career. First I took a Nordic master in medieval studies at the University of Iceland and then I proceeded with my current doctoral work,” say Giulia, who is very happy with life in Iceland.

“Student life here is excellent, I am well received everywhere, both at the University of Iceland and Árni Magnússon institute. I have always been encouraged in my research, and I especially enjoy how close the cooperation is between students and scientists at the University. It is also easy to get to know students from all over the world and various disciplines.”