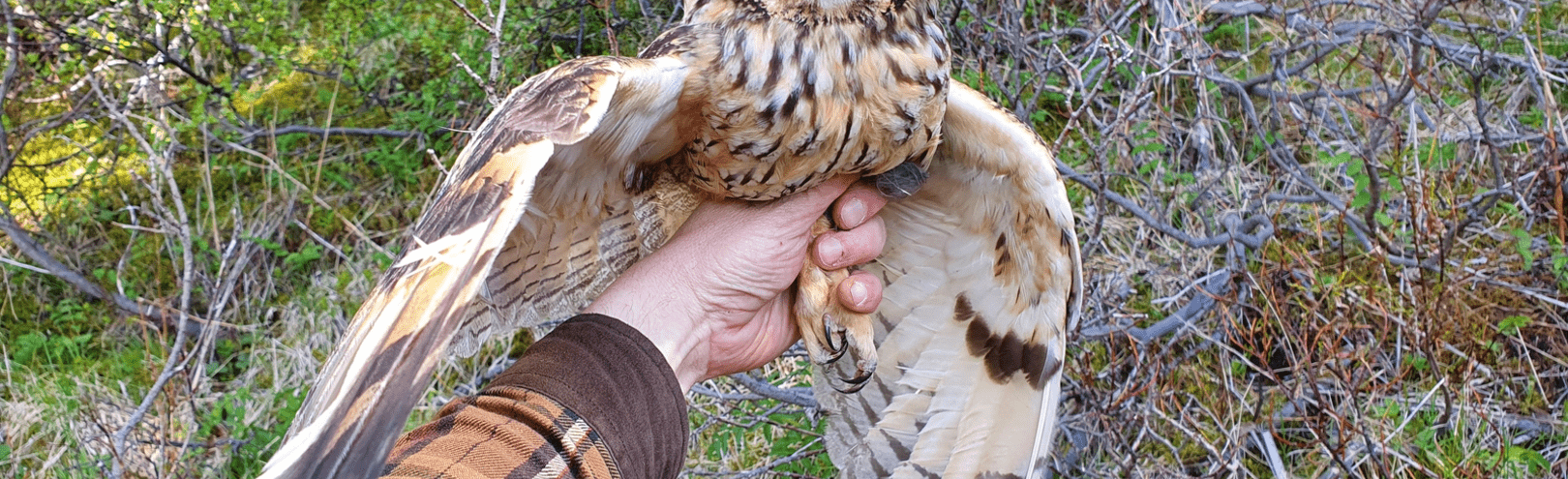

Even though birds are a prominent feature of Icelandic nature, there are species that are not often seen, in spite of the fact that their numbers are slowly growing. The Icelandic sea eagle is thus rarely seen; a species with a low population that has long been threatened with extinction. The sea eagle is now doing better now than in a long time. Owls are also seldom spotted, but two types of owls have succeeded in nesting in Iceland in recent years. It is a worthy question to find out why they are succeeding in Iceland now, however, owls are not easy birds to study. Their behaviour seems to be aimed at staying out of the limelight. “I love owls, and they constantly rekindle a spark that drives me to better understand their lives. When you look an owl in the eye you get a certain sense of mystery and wish to know more. Their secretive habits make it even more exciting!”

So says Gunnar Þór Hallgrímsson, professor of zoology who has dedicated his career to studying eco-systems. He says that such research has never been more important to humanity, seeing how our existence is constantly under more threat.

“It should be clear to all that human society is dependent on healthy ecosystems. Research increasing our understanding of elements that shape the communities of organisms and affect the size of their population and habitats are one of the cornerstones of sustainable development.”

Owls in forests and open spaces

Gunnar Þór has for a large part of his career focused on marine birds, but their fates are interwoven with the marine eco-systems; Iceland’s most valuable resource. Studying the birds that rely on the sea for sustenance is vital, since the state of the marine birds is an indicator on how things are in the sea. Now Gunnar Þór has undertaken a large study of owls in Iceland.

“The owls are interesting in themselves, furthermore it is interesting and important to monitor predators that reflect well the changes occurring in Icelandic eco-systems. The short eared owl reflects the common, open habitats in the lowlands (these areas are shrinking), while the long eared owl thrives in the growing man-made forests shooting up around Iceland,” says Gunnar Þór.

What limits the growth of owl populations in Iceland

The scientist says that the long-term goal of the study is to evaluate the weight of factors that limit population size and the expansion of owls in Iceland. “In the first round we take a special interest in food and habitats. Two of the three owl species that have nested in Iceland are here on the outer limits of their living areas, so evaluating the limiting factors makes sense.”

It may not be a good idea to ask scientist with a passion for birds what sparked the study of owls. Gunnar Þór is fascinated with everything concerning zoology, but since childhood he has had a special eye for birds. “My interest in research was triggered by my interest in birds, rather than the other way around.” He is not reluctant to answer the question on the spark, saying that his interest in researching owls grew steadily over a period of time.

“After having been involved in research on marine and seaside birds for a long time it became apparent that even though it can be convenient to look at the species by themselves, it can be difficult to investigate key factors connected with them, such as food supply. Concerning the owls, I envisioned a lower level of complexity since they feed on fewer species, and it would be relatively simple to monitor the food supply.”

The scientific value of studying owls is twofold, says Gunnar Þór. “On the one hand there is preservation biology involving gathering data on species to predict their future so arrangements can be made if the species runs into problems. On the other the understanding of limiting factors forming the species can provide important information on the condition and activity of ecosystems, theoretically and directly.”

What do owls in Iceland eat?

the next question, naturally, is what do owls in Iceland eat?

“Both species, the long and the short eared owls prefer field mice, but do not reject birds when they are available. For the long eared owl, we see a clear connection between the number of mice in their diet and how well they do in raising chicks, so it seems clear that mice are a key food for them. It is not as obvious how important mice are for the short eared owl, but there is indication that small birds form a larger part of their feed than in neighbouring countries, where the competition with other predators is fiercer. We hope to understand the role of competition in the formation of animal communities by using the owls as models.”

Gunnar Þór says that the first results concerning choice of habitat indicate that the long eared owl is limited by the choice of suitable habitats, but short eared owls seem less hampered in this respect and actually utilise more varied habitats than the scientists expected originally. “The short eared owls seem to be less rooted and are likely to abandon places they have settled in order to seek out new places if the going gets tough.”

Birds are connected to poetry, the living world, and the seasons

Many Icelanders admire birds and connect them to poetry, the living world, and the seasons. Birds are a symbol of their environments, and some of them mean something larger and deeper. The owl is for example a symbol of wisdom, intuition, independent thought, and alertness. To mark this the internal web of the University of Iceland – and a few other universities in Iceland – is called the Owl (Ugla).

The lesser black backed gull, which Gunnar Þór has studied for a long time, is a symbol for the seaside and has become a herald of innovation and adaptation for some people, but a monster for others who observe this new resident in urban areas on lamp posts, picking up chicks that are unable to fly in the surrounding gardens. This bird’s behaviour is an effect of changes in the ecosystem, similar changes have occurred in many birds. Research on birds shows us unequivocally how birds are influenced by the environment and human actions.

Important research for a number of reasons

The scientific value of studying owls is twofold, says Gunnar Þór. “On the one hand there is preservation biology involving gathering data on species to predict their future so arrangements can be made if the species runs into problems. On the other the understanding of limiting factors forming the species can provide important information on the condition and activity of ecosystems, theoretically and directly.”

Gunnar Þór says research is vital. “High quality research increases our knowledge and understanding and can thus increase the chance for humanity to survive and prosper.”