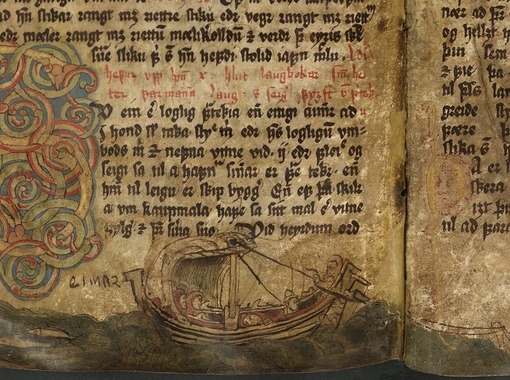

Icelanders are fortunate in having written about themselves a short while after the country was settled. The fact that this material has been preserved is remarkable. This literature is of unique artistic value, and furthermore provides a glimpse into the lives of the people who wrote it; and insight into the cultural origins of a whole nation.

Torfi H. Tulinius is a professor of Icelandic mediaeval studies at the University of Iceland and leads the international master programme in the subject. He spends much of his time studying our medieval literature. This is important because “research in the humanities tackle the products of the human spirit, deepen our understanding of them, and open our eyes to their endless variety,” in the words of Torfi himself.

He asserts the sagas have long informed our understanding of who the Icelanders are. “Times change and Icelandic society has undergone more changes in the last century than ever before. We need to rethink our identity. One way to approach this is to revisit our literary legacy. Furthermore, this particular legacy is globally unique, with value that stretches way beyond our shores; thus understanding the Icelandic literary tradition enhances our knowledge of global literature.”

Searches for Trauma

Torfi is now scouring the stories of the original settlers in the sagas and Landnámabók looking for all signs of trauma connected to the settlement. This is not light material since the themes include enslavement, bereavement and loss of wealth and social status.

„These narratives are written more than two hundred years after the events themselves, but still give a certain picture of social circumstances in Iceland in the 9th and 10th centuries CE,” says Torfi. “However, they are a better source on how the authors and readers of the sagas in the 12th, 13th and 14th saw the past in the light of their own present.”

The traumatic societies that begat great literature

Torfi says that a lot in this literature indicates that the society that begat it struggled with a variety of trauma. The past that is sketched in the works is characterised by loss of homeland, social standing and even a good life in a fertile country.

“In the narrative of Landnáma and the sagas it often seems that the social standing of a person is determined by the location and extent of the settlement; or whether he or his forefathers has settled land or had to get land from former settlers. Social standing is thus at times lower than the character’s self-identity indicates. These stories from the past are probably told because they reflect the social realities of time of writing in the 13th and 14th centuries, not least the extreme violence of the age of Sturlungar.

“Times change and Icelandic society has undergone more changes in the last century than ever before. We need to rethink our identity. One way to approach this is to revisit our literary legacy. Furthermore, this particular legacy is globally unique, with value that stretches way beyond our shores; thus understanding the Icelandic literary tradition enhances our knowledge of global literature,” says Torfi.

Applies methods from a variety of disciplines

Torfi is a productive researcher, primarily in the field of Icelandic medieval literature, especially Legendary Sagas and Icelandic Sagas. In his analysis Torfi uses an interdisciplinary approach. He has used narrative studies, sociology, history, semiotics, reception theory, and even psychology to deepen our understanding of the role of the works in the society that produced them.

“Yes, you are right,” says Torfi, “interdisciplinary research on cultural products, especially literature, where sociology, psychology and history are applied to enrich and deepen literary studies; this is my main field of interest. Since I began studying medieval literature I have been interested in how it spoke to their contemporary readers. I have always been interested in how various narratives mirror divergent values and tension between social groups. My research on the Legendary sagas at the beginning of my career shows this well. Since then I have dug deeper into narrative structure and meaning creation in the Legendary sagas and concluded that psychological and social factors are intertwined in the sagas. In this context my interest in the terrible traumas occurring in Icelandic society was piqued; not least in the 13th century. How the view of the past is informed by this trauma in the Icelandic sagas and Landnámabók is fascinating.”

A prolific scholar

Torfi has been prolific in writing articles and books based on his research. This year he has published three book chapters in academic books, all connected to this subject. “The first one is about the identity of the 13th century Icelander and how it is marked by tension between social and religious values, and how this tension shapes narratives, both about contemporary conditions and the past.

In the next one Eyrbyggja saga is scrutinised and the efforts of leading families to redefine their social position in a changing society read into it. The third one explores different genres of narrative mediaeval literature, and how each genre connects to the realities of 12th and 13th century Iceland. I am, along with two of my colleagues, currently putting the final touches to an article on social anxiety that can be found in medieval literature.”

Scientists like Torfi often consider the inherent value of research as a motivation in their work. “Research has value in many diverse ways,” he says. “Increased knowledge can lead to progress in all fields: technology, science, society. The training and education needed to do research enhances the ability to think clearly and critically about reality, to discern what is of value and what is not – and to see through deceit when needed.”

This concluding point is of great importance in our times, when fake news pops up at the speed of light all over the world.