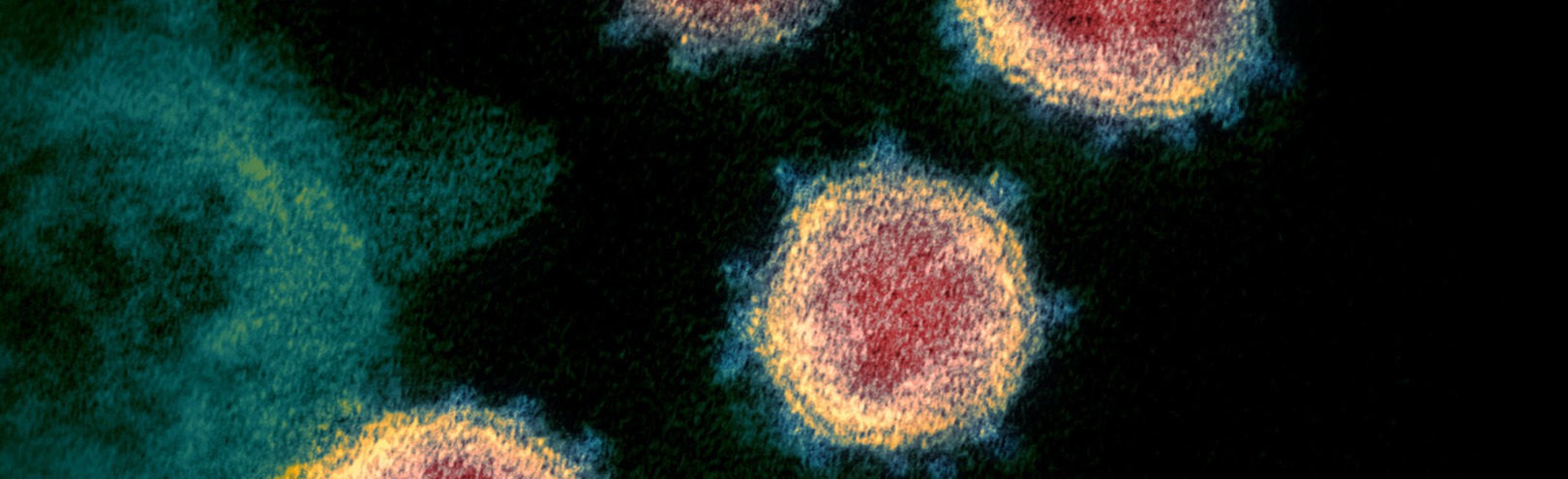

In light of the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 and the serious economic and public health consequences that it has had across the world, many people have wondered whether human behaviour could partly explain how this happened, both how the virus was originally transmitted to humans and how it then spread across the world.

Magnús Gottfreðsson is professor of infectious diseases at the University of Iceland and senior consultant at Landspítali University Hospital. He says that yes, there has been a change in the way viruses behave, or rather how they are transmitted to humans.

"Firstly, humans are quite an aggressive species," says Magnús, "we have taken over a large part of this planet we live on. We have invaded ecosystems that are rather complex and have been isolated for thousands of years. Humans have cleared forests and eaten various animal species that are not adapted to living alongside us. All this increases the chances of contact between two worlds: our world and the enormous, complex world of the microorganisms that live in these ecosystems."

Magnús says that when people are constantly expanding their habitats and taking over forests and ecosystems in a very broad sense, there will be conflict and the frequency of this conflict has been increasing.

"We live close together, we live in cities. We travel on places, trains, subways, we go to football matches where a hundred thousand people come together and everyone is singing. All this dramatically increases the chances that pathogens will spread," says Magnús Gottfreðsson.

Population growth and travel increase the risk of disease spreading

"To add to this, we humans are multiplying. There are an incredible number of us on this planet: 8.6 billion. The third factor is that we are now able to travel around the whole world within 24 hours. All these ingredients come together, meaning that if someone comes into contact with a new pathogen, there is a much higher risk of it becoming something more than a localised issue."

Magnús says that over the centuries, of course it has happened that people have been unlucky and been infected with certain pathogens and either recovered or died. There were not really any further consequences.

"But today the picture is quite different. We live close together, we live in cities. We travel on places, trains, subways, we go to football matches where a hundred thousand people come together and everyone is singing. All this dramatically increases the chances that pathogens will spread," says Magnús.

He says that the higher risk is not just in the infected individual's immediate community; pathogens may potentially spread far beyond that individual's own borders and even across the world within 24 hours.

"I think most people who research these issues agree that this problem is here to stay, because it is very difficult to reverse this course. It is not impossible and I think people will probably now be more conscious of the problem and try to reduce the risk as far as possible."