When the poet Jakobína Sigurðardóttir heard that the US Army intended to use the bird-nesting cliffs in Hornstrandir for target practice, she wrote a verse urging the landscape of her beloved childhood home to frighten and drive them away. Jakobína grew up on the remotest shore of Hornstrandir at Hælavík, where potatoes would not grow in the salty soil and the family lived through frequent storms and hard times. Spring was often late to arrive and sometimes summer never came. The pack ice could be seen just off shore, sometimes extending right into the bays.

Jakobína was born at Hælavík 8 July 1918 and died 29 January 1994. The farm where she grew up is now a ruin of a ruin. The sea has claimed almost everything that was once a building, leaving no trace. These days, children are no longer born to people who can say they are from Hælavík or Hornstrandir. But where are we from? Where did we come from? Who is from Hornstrandir and what does that mean? Where is their home?

Guðrún Svava Guðmundsdóttir, PhD student in geography at the University of Iceland, is working on a project that seeks to answer these questions and many others. She argues that when people define their place in the world, they put the past into the context of the present, which then follows them into the future.

"Like the question, where are you from," says Guðrún. "For example I grew up in Stykkishólmur. My daughter, who grew up in Reykjavík and Ísafjörður, also identifies as being from Stykkishólmur. Where am I from and where is she from?"

These are certainly interesting questions, but we will have to wait a while to read Guðrún's conclusions, as her thesis is still a work in progress.

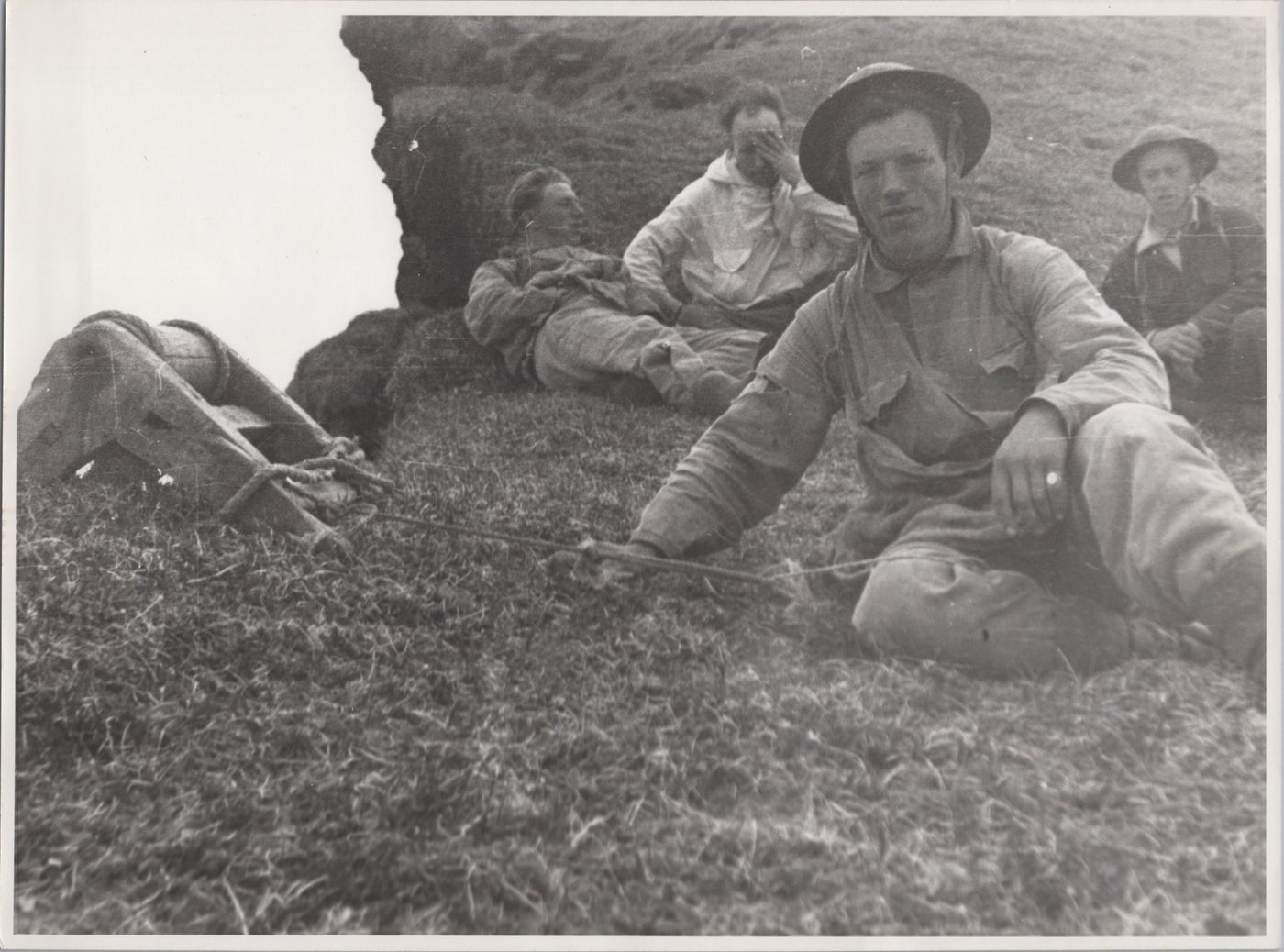

Habitants of Hlöðuvík in Hornstrandir included the brothers Bergmundur Guðlaugsson (1918-1990) and Þórleifur Bjarnason (1908-1981) and their mother, Ingibjörg Guðnadóttir (1888-1970), standing between them. They were half brothers on their mother's side. IMAGE/Ísafjarðarbær

Researching three generations from Hornstrandir

Guðrún's PhD research looks at three generations from Hornstrandir, using three different methods based on photography to explore what it means to 'have a home in the world' and how ideas about 'belonging' change across time and space.

"The question of where your home is isn't just about a physical location. It's based on a complex web of experiences. I am looking at how heritage relates to the idea of 'belonging' and how people create a certain place in the world that they feel is theirs," says Guðrún.

"I've always been fascinated by people and how they define themselves. So the idea of 'belonging' and what it means to 'have a home in the world' are very interesting topics for me."

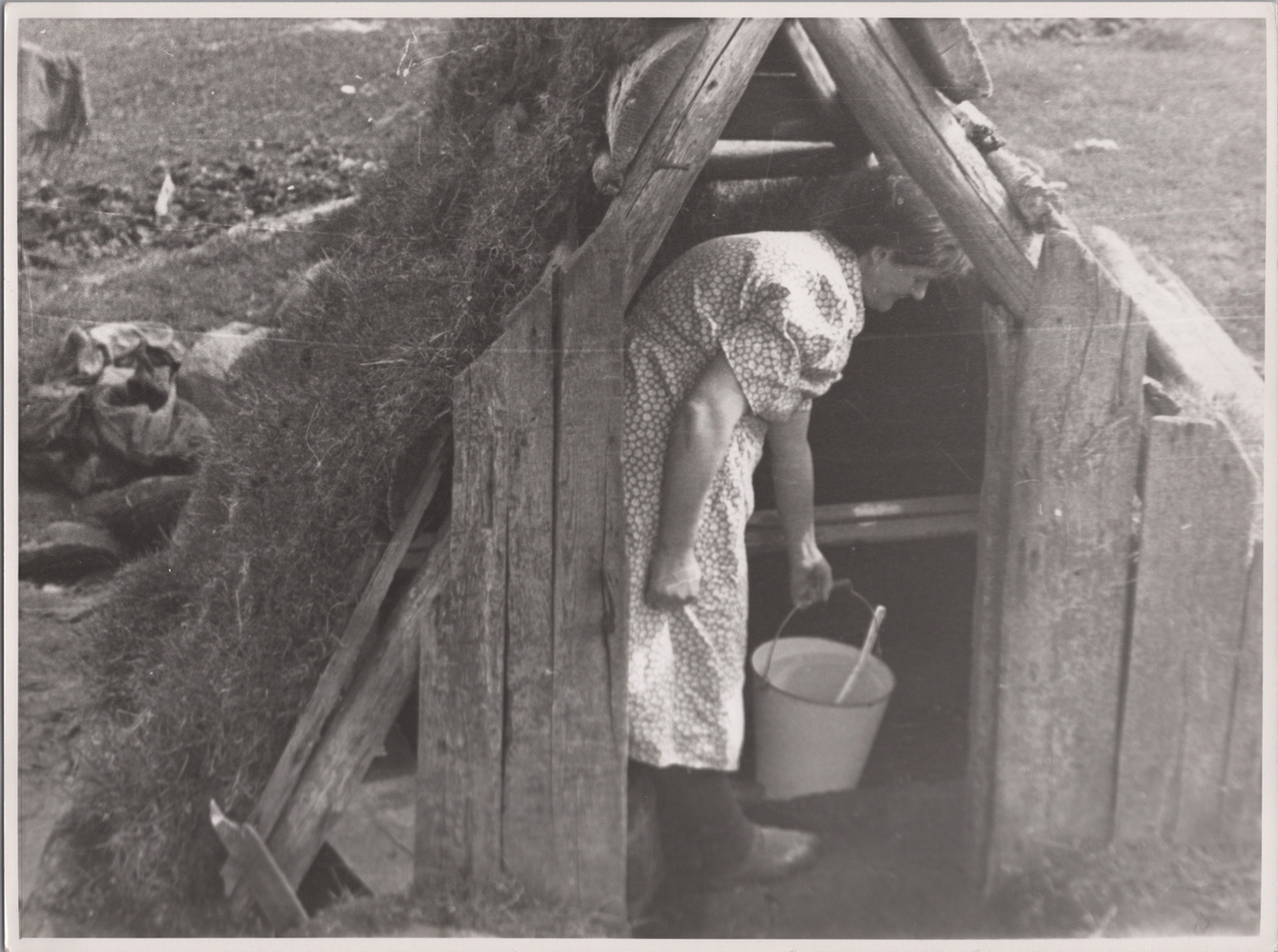

Hornstrandir is an extremely beautiful place as those who have hiked there know all too well. IMAGE/Jón Örn Guðbjartsson

Hornstrandir is unique

Visiting the abandoned Hornstrandir is a moving experience for most people. Travellers often feel as though they could be the first to ever set foot in that vast empty wilderness. The landscape is striking, with its dramatic cliffs and precarious pathways formed gradually by successive generations. In Hornstrandir, you can find sheer peaks and columns of rock, vast golden beaches, rivers and estuaries, streams, waterfalls and lakes. Even a glacier!

Hornstrandir has been a nature reserve since 1975 and human impact on the landscape has been kept to a minimum for almost half a century. Some areas of the reserve have never been settled by humans, such as Sópandi in Lónafjörður, which probably looks about the same today as it did when humans first arrived in Iceland. Perhaps in some sense all Icelanders are coming home when they come to Hornstrandir, seeing the country as it appeared to their ancestors.

"How did the first settlers find a home, a place in the world they could call their own, far though it was from the land of their birth," wonders Guðrún. "That's precisely what the people of Hornstrandir had to do, to make a new home far from where they were born. When do we belong to a place, a group of people or a community? How does that happen?"

In Hornstrandir, people's livelihoods depended on the sea, but the sea was also the force that swept the people away. Visitors can see abandoned villages, renovated buildings and ruins that bear witness to an incredible history, but also the end of a community. All this contributes to the way people from Hornstrandir think about what it is to 'belong', to be 'at home'.

The abandonment of Hornstrandir

When people began to desert Hornstrandir in the early 1950s, they were scattered across the country. Some went south, while several families started a new life in Bolungarvík, which is geographically the closest community to Hornstrandir. People moved away from Hesteyri and the northern bays in 1952. Grunnavík was abandoned in 1962. Aðalvík was still inhabited up to 1963, when the US Army had a base at Straumnesfjall. A few Icelanders lived in Aðalvík, working for the army. However, that life was very different to the tough and self-sufficient lives that Icelanders had endured for centuries in Hornstrandir.

"The British Army, who arrived in Hornstrandir before the US Army came, became the main source of income for young people in remote settlements. It was a huge change for the area. My interviewees talk a lot about 'the British', referring to the British occupying forces who had a base at Darri in Aðalvík. There were also others who moved to avoid the disturbance of the military operations and training drills, although often they simply moved to other places in Hornstrandir rather than leaving altogether. The fate of the region was sealed when the young people left and there was nobody to take the places of the older people when they couldn't work anymore," says Guðrún.

"My research could also contribute to public debates about the importance of maintaining communities across Iceland and provide new angles from which to consider those issues. For example, whether there should be more government grants to enable people to live independently in the landscape they choose," says Guðrún.

Interviews uncovered the wonder of Hornstrandir

Guðrún first became interested in Hornstrandir when she was working on her Master's project at the University of Iceland: Family photographs. Manifestations of people in their environments. It so happened that she completed this project in Bolungarvík and talked to a lot of people who mentioned Hornstrandir.

"My interviewees would tell me they were from Hornstrandir or this person or the other was from there. That's what sparked my interest in Hornstrandir and the people who had lived there. I soon realised that the number of people who had lived there and moved away was rapidly dwindling, since the region was abandoned around the middle of the last century. So I set myself the goal of interviewing as many people as possible who could share their experiences of living in Hornstrandir, leaving and making a new home in a new place. I was also interested in the question of what happened next for these people."

We see the past in a certain light

Guðrún is still collecting data, but she is clearly something of a pioneer in her doctoral research. Except she is not exploring the land as it is now – but rather as it was. We are in danger of losing the past, because not much has been written about life in Hornstrandir. There is therefore a kind of urgency about this project, which will shed light on how we relate to the past and who we are. People are telling stories that have probably never before been told or written down.

"We often see the past in a specific light," says Guðrún. "When we talk about heritage or historical events, we always make choices about what to remember and what to forget. The past becomes the present in the act of remembering. Distance from the place, the community, leads to a sense of belonging to a landscape, whereby people recreate their environment either in the physical or spiritual sense."

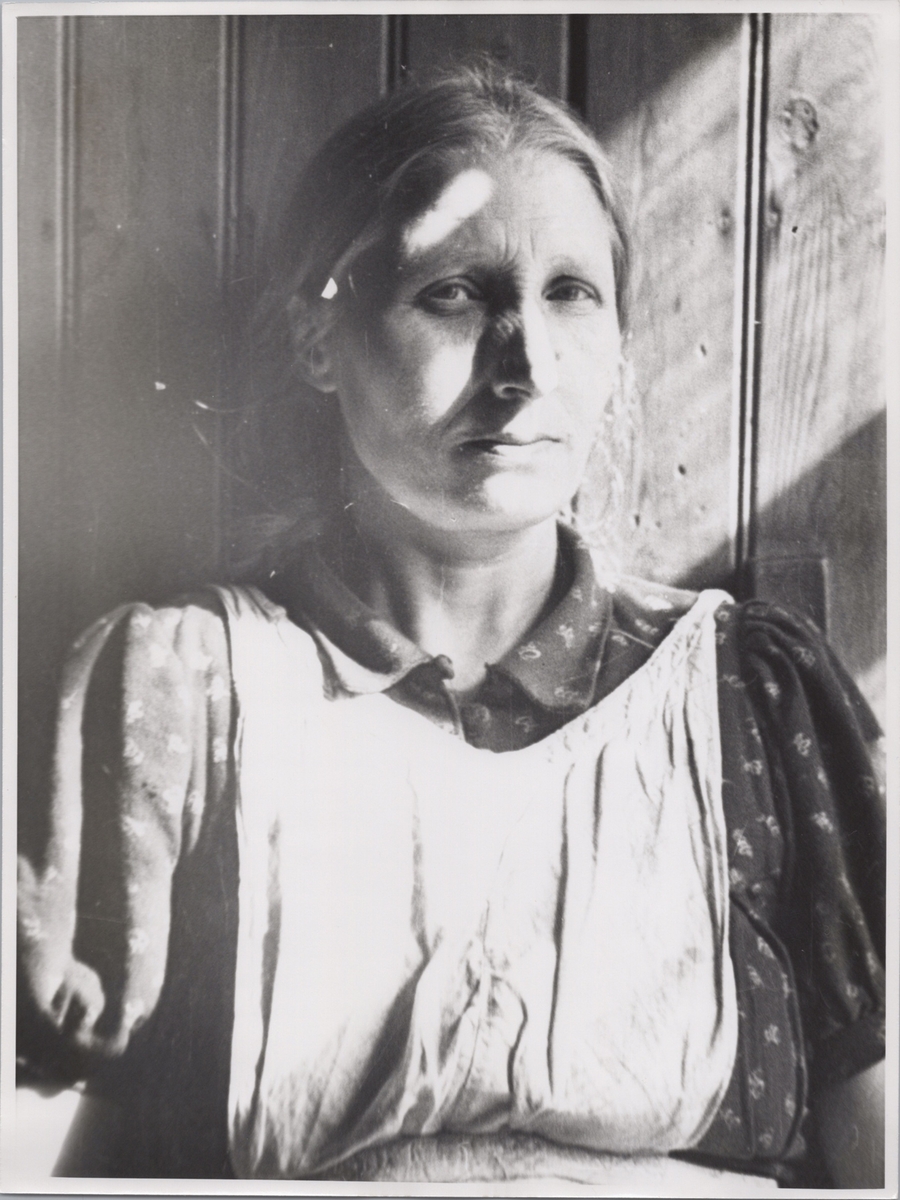

"Heritage is not just something in the past that we talk about," says Guðrún. "It evolves across time and space. IMAGE/Jón Örn Guðbjartsson

Guðrún argues that distance from a place and a landscape also creates intimacy and is part of 'belonging'. "For a long time, I felt as though I had spent most of my life in Hornstrandir, but that's not really the case... I'm almost 64 and I was there for 11 years, so I haven't lived there for 53 years. But my memories of Hornstrandir are incredibly strong. They are a huge part of who I am." (Extract from one of Guðrún's interviews)

Guðrún is collecting stories from interviewees across Iceland. There are many stories of how people abandoned Jökulfirðir and Hornstrandir, areas that had been inhabited for centuries, because life was no longer sustainable.

One story tells of a meeting held one evening in Hesteyri in Sléttuhreppur district, where the residents held a vote on whether to leave or stay. They voted to leave. Some people left belongings behind when they abandoned their houses, since it was not possible to transport everything by sea. When travellers arrived years later and peeked into the empty houses, many strange sights met their eyes. Even coffee cups seemingly abandoned on the kitchen counter in a hurry, with lip marks still visible, as though awaiting the return of their owners' lips. The strange thing is the inconsistency, that some people left so much behind while others brought their actual houses with them.

"There's still a connection with the district, Sléttuhreppur – we say the old Sléttuhreppur district. It's gone now, except in memory. It's Ísafjarðarbær now." (Extract from one of Guðrún's interviews).

There is another story of when the couple at Reyrhóll in Hesteyri, Sölvi Betúelsson (born in Hesteyri, 30 January 1893, died 13 August 1984) and Sigrún Bjarnadóttir (born in Aðalvík 22 September 1905, died 2 May 2001), who were the last remaining people in Hesteyri, finally abandoned their farm. They took both their cows with them and settled in Bolungarvík. The story goes that the cows began to give much less milk than before. The next spring, the couple went home to Reyrhóll for the summer with one of the cows. According to Sigrún, the cow rejoiced at the return with much gambolling and began to give much more milk as soon as she got home. Perhaps we all feel a little like Sölvi and Rúna's cow when we arrive home.

It is a little strange that although Sölvi was born in Hesteyri and lived there for a large part of his life, had his home there, he was said to be from Höfn in Hornvík. That is no doubt one of the things that Guðrún will explore in her research.

"Heritage is not just something in the past that we talk about," says Guðrún. "It evolves across time and space. Heritage is that which was, that which is now, and that which will be. I believe it is important to learn from the experiences of the people who lived in Hornstrandir, where the self-sufficient way of life slowly ebbed away until the people packed up their belongings and left."

New knowledge that will be public and accessible

"By combining visual approaches in a critical way, I hope to lay the groundwork for making better use of them in research," says Guðrún.

"My research could also contribute to public debates about the importance of maintaining communities across Iceland and provide new angles from which to consider those issues. For example, whether there should be more government grants to enable people to live independently in the landscape they choose," says Guðrún. She also believes her research is relevant to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

"The communities in Hornstrandir were sustainable, until they began to decline and were abandoned. They show us very plainly how important it is that communities are sustainable so that they can survive and flourish."

Guðrún's supervisors are Katrín Anna Lund, professor of geography and tourism studies at UI, Edda Ruth Hlín Waage, senior lecturer in geography and tourism studies at UI, and Arnar Árnason, senior lecturer in anthropology at the University of Aberdeen.