The University of Iceland is an open and international university where diversity is a priority. Over 1,500 international students from 100 countries study here. One of these is the doctoral candidate Mohsen Rafiei from Iran. He works on research in perception science at the University of Iceland’s Visionlab and will defend his thesis 10 December 2021.

Árni Kristjánsson, professor of psychology is Mohsen‘s main supervisor. Árni has primarily researched the human visual system, exploring how our attention and visual perception work together. Mohsen’s current project is to map out various tricks the brain uses when it comes to visual perception.

“Yes, I am born in Iran,” says Mohsen, and adds smiling that magnificent pristine nature can be found there, just like in Iceland – along with ancient culture and history, great food, and friendly people.

“I grew up with my wonderful parents and sister in Arak, a large industrial city in Iran. I finished my basic education there,” says Mohsen, who is also a proficient musician, his instrument of choice being the tanbur, an Iranian string instrument. He founded a band in Iran, and sometimes finds the opportunity to play in Iceland. His main passion is the science of perception, and this interest drew him all the way north to Iceland.

“Yes, it is remarkable,” says Mohsen and smiles. “Even though Iceland is a beautiful country with pristine nature the main attraction for me was working with Árni Kristjánsson at the University of Iceland. He is a well known and respected scientist internationally in the field I have chosen, perception science.”

The brain uses to tricks to simplify our perception

Concerning the doctoral study Árni Kristjánsson says that the human visual system needs to process an enormous amount of information that comes through the eye every moment they are open.

“Actually, the amount of information is so extensive that the brain has problems processing all of it. The visual system therefore uses various tricks and simplifications to process visual data. The visual system for example uses prior events and uses them to evaluate the stimuli in each moment.”

Árni says that Mohsen’s research clearly shows how our perception in each moment is dependant on what was seen in the moments just before.

“The brain uses prior experience or knowledge to weed out the chaos in the information the eye receives. I am interested in finding out what process this is in the brain and what neurological systems are involved,” says Mohsen.

Árni explains this complex perception process by referring to an experiment where the participants are shown a line with a certain incline and are subsequently asked to recreate the line’s incline on a computer screen. “The participants’ evaluation of the incline is influenced by stimuli from moments before they saw the line. This simple experiment shows how our perception not only reflects what the eye receives here and now, but also what we have recently seen.”

Árni says that the visual system thus assumes that the world around is not dynamic, but that stimuli in our environment recently are likely to stay the same, rather than new ones taking their place.

“Tricks like this,” says Árni, “make the visual system’s work easier, but can simultaneously lead to perception errors. This is rare, because the visual system is right in assuming that the world is not constantly changing. The things around us just recently are likely to remain so, though this may not always be the case.”

Mohsen says that everything we see is our personal interpretation of the multifarious light patterns that land on our eyes. “Why personal? Well, see, this is because everything you see is connected to older information in the brain and you prior experiences. I want to know how and why our perceptive history influences what we see.”

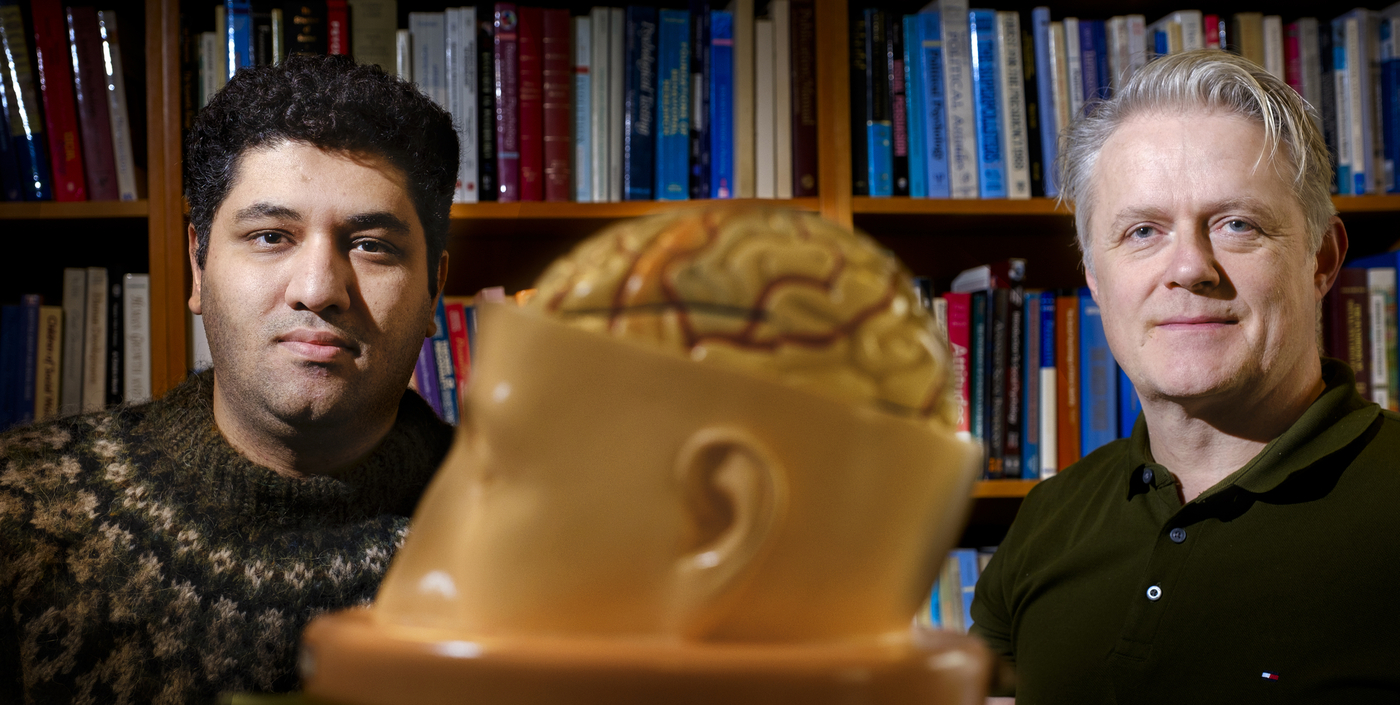

“The brain uses prior experience or knowledge to weed out the chaos in the information the eye receives. I am interested in finding out what process this is in the brain and what neurological systems are involved,” says Mohsen Rafiei, PhD student who is here with his supervisor Árni Kristjánsson. image/kristinn ingvarsson

Our brain is partial

One of the questions Mohsen and Árni grapple with is to what extent we can gain control of our memories, of what we know. Their research shows that the human brain uses former perception to create a variety of subjective perceptions to facilitate finding and sensing interesting things.

However, control over such processes can be vital, for example in situations where professionals review and evaluate information.

“By studying the brain’s partiality we can find ways to train professionals in many fields to avoid these automatic processes while they for example review new roentgen images of a patient to detect signs of serious illness,” says Mohsen. Árni points out that there is always a risk that an individual’s perception history may cause them to miss signs of fatal diseases, even if clearly visible in the image in front of the specialist – because their brain may recall older images of the same patient where no such signs were present.

The innovative aspect of the research and its social impact is clear here; helping people find and perceive things correctly without the biases of experience getting in the way.

Employed by Adidas

After finishing his doctorate Mohsen will take up a position at the research and development department of Adidas at Arisona State University. Árni says that companies like Adidas can utilise knowledge on how the brain processes perception in developing their products and in scientific work connected to their products. “Mohsen will use virtual reality in his research at Adidas, equipment that we also use in our research centre. Researchers in neuroscience and in perception psychology learn a great deal in methodology, statistics and programming and have extensive experience in research that can prove useful in R&D and various innovation. Executives in companies like Adidas know this and are keen to hire people with such backgrounds.”

Got a culture shock just after they arrived

Before moving to Iceland Mohsen had never left Iran. He is not alone here because his wife Bahareh is also a doctoral candidate, researching visual factors in dyslexia and prosopagnosia (face blindness), supervised by Árni and Heiða María Sigurðardóttir, associate professor of psychology at the University of Iceland.

“In the first months after arriving in Iceland we experienced a culture shock, because everything is different here, from how people greet each other to how they enjoy the short days in December. But after having lived here for four years and learning from our Icelandic friends about your culture and history, our mindset changed, and we learned to enjoy Iceland, even when it is dark and cold outside! When you leave your country for a new one it is important to learn about and respect the new culture, this enriches your life and makes it much more interesting!”

Mohsen is happy with the University of Iceland and says that the country is ideal for study and research. “Almost everyone speaks English here, so international students can adapt to society and make friends. Nevertheless, I strongly recommend learning the language, which is beautiful and with ancient roots, because this provides an excellent connection to Icelandic culture.”

Mohsen says that doctoral candidates are better paid in Iceland than in many European countries, making students’ lives much easier. “Iceland is also a very safe country, and you can go for a midnight walk without fear or trouble. People are friendly and generally open. On the whole living and studying in Iceland is a great experience.”

Mohsen’s supervisors with Árni Kristjánsson are Andrey Chetverikov at the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour at Radboud University in Nijmegen, and Sabrina Hansmann-Roth at Université de Lille, who both have done post-docs at the Visionlab at the University of Iceland.

Mohsen’s research is funded by the Icelandic Research Fund through a grant received by Árni Kristjánsson and Andrey Chetverikov, and with a doctoral grant from the University of Iceland Research fund.