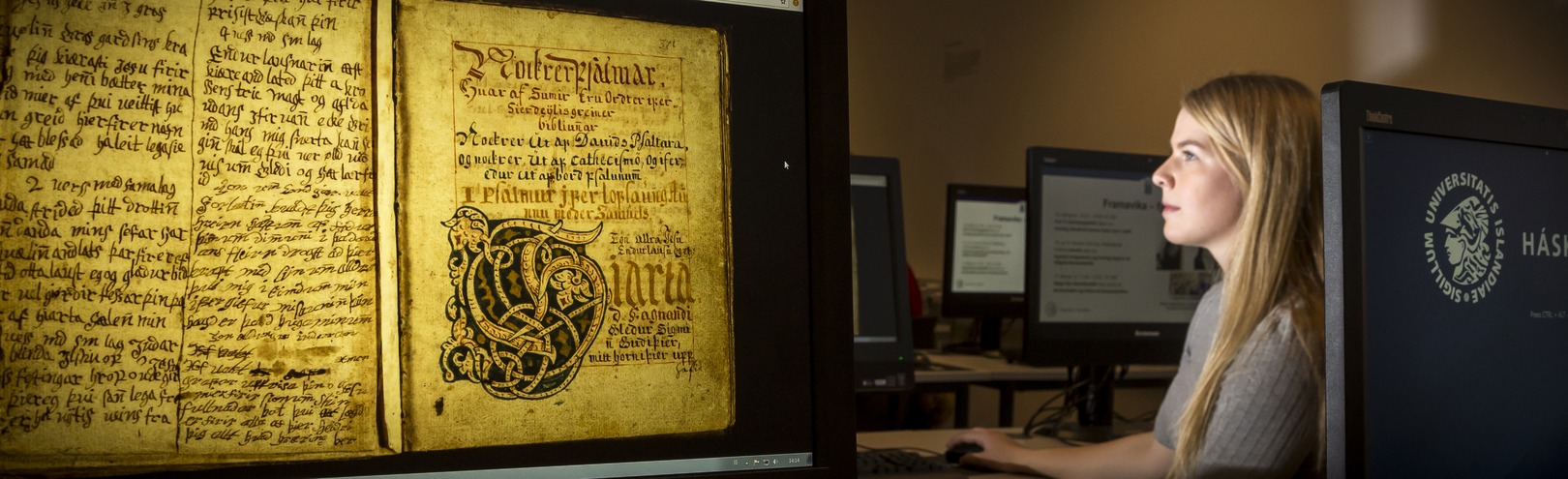

Scientists and students at the University of Iceland have been contributing in various ways during this enormous social upheaval caused by the COVID-19 epidemic and the recent assembly ban in Iceland. Among them is Guðlaug Marion Mitchinson, a PhD student in psychology at the University of Iceland, who has used her specialist knowledge to translate and adapt educational material about the virus for children. The material has spread through the community like the virus itself and has attracted significant attention from the media.

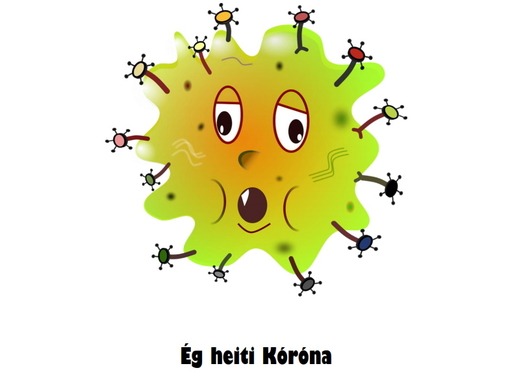

It is an illustrated story about the virus 'Kóróna', who likes to travel from person to person. The author of the original version, which was published in English under the title COVIBOOK, is Manuela Molina. Guðlaug came across her story when searching for ideas for educational material on the epidemic for children. "Seeing how well the Department of Civil Protection, the Directorate of Health, healthcare professionals and the media were keeping the public informed about COVID-19, I thought it might be possible to put together some simple educational material for children. This was something I was thinking about particularly, because I work as a child psychologist for the Department of Education in Kópavogur. A short while later, I was lucky enough to find COVIBOOK and decided to translate and adapt Molina's material, with an emphasis on functionality so that children would find it easy to connect with the story and understand it," says Guðlaug, who obtained permission from the original author for the project. "It just so happens that I wasn't the only one who had this idea, because Christína van Deventer and Bragi Þór Valsson translated it into Icelandic as well.“

Guðlaug praises Molina's work and points out that the author has done her best to ensure that children, parents and guardians can access the book for free in as many languages as possible. It is now available in 24 different languages on the author's website.

Encourages children to discuss their worries

"I translated Molina's material and also adapted it to the situation in Iceland, aiming mainly at preschool children and young primary school children, since these are the ages I work with for the most part. I also wanted to highlight how important it was for children to turn to guardians and school staff to discuss any worries they might have. Some children are good at telling adults how they feel, but there are also children who hide their worries and I wanted to try and reach them too," says Guðlaug.

The response to Guðlaug's brilliant initiative has been overwhelming: "I never dreamed the story would become so popular. The demand for such educational material here in Iceland was much higher than I initially realised. I have been following Manuela Molina on her Instagram channel (which is called Mindheart.kids), and the response has been similar all over the world. The situation around the world is, to put it mildly, full of uncertainty, which is challenging for most people. It is important for us all to stand together at times like these," said Guðlaug.

The illustrated story that Guðlaug translated and adapted to the situation in Iceland is about the virus Kóróna and how she travels from person to person. IMAGE / Manuela Molina

Books provide a good starting point for discussion

As previously mentioned, Guðlaug works as a child psychologist alongside her doctoral studies at the University of Iceland. She says that it is important for parents to shield their children from a never-ending stream of press conferences, news stories and announcements about the epidemic. "The media often uses complicated words that children may misunderstand or misinterpret, which may make them more worried and insecure. We shouldn't keep all information about the virus from them, but instead use the knowledge that we have acquired to discuss the subject calmly with children, using language that is appropriate for their age and maturity. I generally advise parents to read books with their children about various topics and use them to start a conversation afterwards," says Guðlaug, pointed out that the material is ideal for this purpose.

"It is also important to remember to take one day at a time. Children are not necessarily thinking far into the future, like we adults do – they just need to know what is happening today and tomorrow. It's good for guardians to maintain routines as far as possible, get up and go to bed at similar times, try to have a routine for meals and exercise. Also set aside a time to go over their homework or other organised activities. Don't forget to spend quality time together and remember that some days it won't be possible to stick strictly to the routine. Finally, it is important to slow down when we can and do something that the children enjoy," she says when asked how parents should manage in these unusual times when so many of us are at home so much.

Furthermore, she points out that the Directorate of Health, Heilsuvera, health clinics in the Reykjavík area and others have recently shared good educational material for children and adults. "Several people on Facebook and Instagram have also been sharing fun ideas for learning activities that children can do at home and advice on how to maintain routines in quarantine. For example, Hlín Magnúsdóttir in Njarðvík has shared a huge collection of brilliant activities for children to do at home, both on Instagram and Facebook, called "Fjölbreyttar kennsluaðferðir fyrir fjöruga krakka". Psychologists and speech pathologists at the School and Welfare Department in Árnesþing also have an Instagram channel called "heimaskolinn", which has some really good tips," she says.

Emphasis on children's feelings

Guðlaug's experience in her PhD project was extremely useful in creating educational material about the virus, since her work focuses on managing emotions, something that is much under discussion at the moment. "The goal of my doctoral research is to map atypical emotional regulation and the development of behavioural problems in Icelandic children aged 5–8. Since I read a lot of studies about the consequences of atypical emotional regulation in children, I have automatically started focusing on this in my work. For example, I am helping guardians to improve children's skills in emotional regulation and emotional literacy. When I started thinking about putting together educational material for children in these uncertain times, I wanted to focus on children's emotions and whether they can identify them, because then we adults can try to help them deal with uncertainty and unhappiness," says Guðlaug.

Guðlaug is the first person to conduct a long-term study into emotional regulation and behavioural problems among children in Iceland. "We have just finished gathering the data, having followed a cohort of children born in 2010 and 2011 for three years. The findings based on all the data will soon be available, which is very exciting," conclude Guðlaug.

Guðlaug's Icelandic version of the story about the coronavirus is available here.