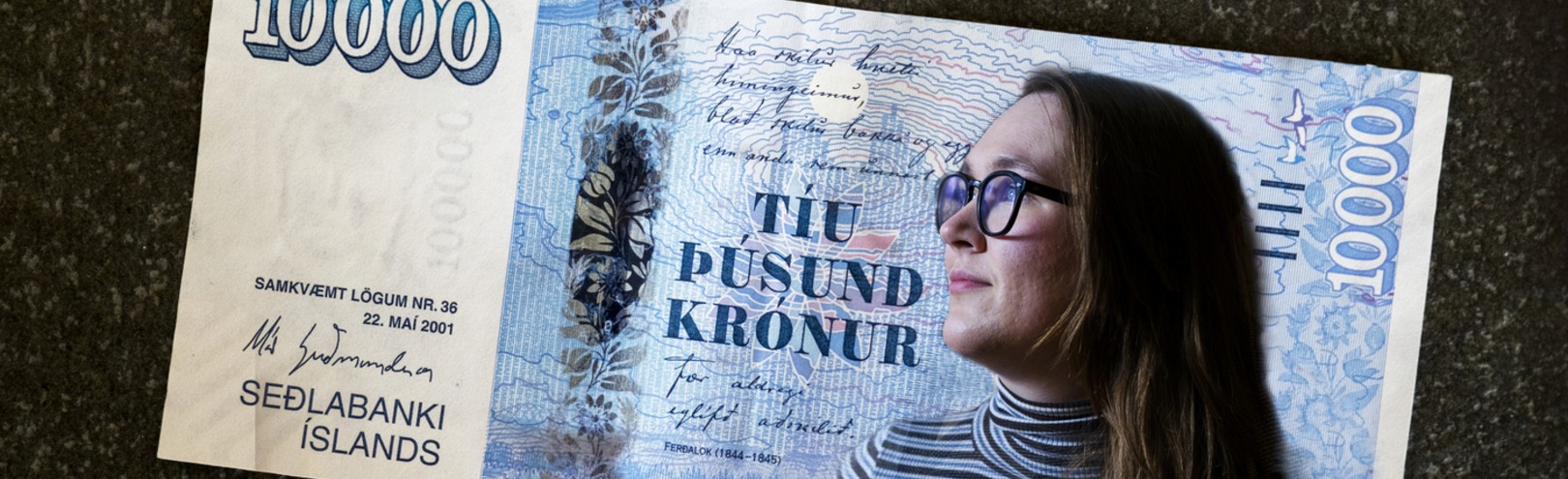

The search for happiness is as old as mankind and a diverse group within the scientific community has tackled the conundrum of what makes us happy. Artists have also wondered for a long time. "Does beauty create happiness?" asked the Icelandic pop star Bubbi Morthens whilst another singer claimed that the happiness was "here". But can money make us happier and is there any way to evaluate how much money we need to be content with our lives? Guðrún Svavarsdóttir is tackling this mystery and other questions in her doctoral studies in economics at the University of Iceland.

"My doctoral thesis is divided into three parts that all discuss the connection between income and happiness or welfare, but in different ways," explains Guðrún who will write scientific articles for each part to be published in journals, a widespread method in the scientific community. "In my first article, the only one that is almost complete, I study two aspects of this relationship by using extensive data from Russia. First of all I look at how much income people need to reach a certain level of welfare. It is possible to examine what factors might have an impact on income needs in this context."

Higher income seems inevitably lead to people wanting more

Guðrún points out that prior research show that real income has an impact on how much people think they need. Individuals with more income thus think they need a larger sum to obtain the same level of welfare as individuals with a lower income. "My results show this too, a higher income seems to lead to people considering they need more," she says.

Secondly, the focus of Guðrún and her associates is on the so called welfare sensitivity; e.g. to what extent people's welfare changes when their income changes. "In other words, if I get an extra 50 thousand krona, how much happier will I be? This varies between individuals. Both have been researched to some extent, however, it has proven difficult to explain why welfare sensitivity varies between individuals. In the article we study at whether external factors; e.g. other than individual differences such as gender, age, job etc impact this complicated relationship between income and welfare," says Guðrún.

Guðrún and her colleagues used a method developed by the economist Bernard van Praag to answer these questions, but it enquires how much income people need for different levels of welfare. "For example: "How much income would you need to feel that your family was poor, average or rich?" Peoples' answers to this question on income are then used to evaluate a so-called individual welfare function of income providing these two variables; income need and welfare sensitivity for changes in income for each individual. If the questions are a part of a larger survey it is possible to examine what social factors impact these variables," she says.

Data from Russia form the research basis

It is interesting that the data comes from Russia as the Russian community is generally considered to be divided according to class and in many ways unlike western societies. The data is from the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey from the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. "The part of the data we use holds answers from over 10 thousand individual living all over Russia. This enables us to see whether external factors such as income equalization and gross national production (GNP) which varies depending on where in Russia you live, influence income needs and welfare sensitivity without having to worry about whether different currencies or languages distort the outcome, as might happen if we compare results from different countries in Europe," explains Guðrún who was working on the study with Tinna Laufey Ásgeirsdóttir, professor of economics at the University of Iceland and Guðrún's supervisor, and Andrew E. Clark, professor of economics at the Paris School of Economics, and Gunnar Stefánsson, professor of statistics at the University of Iceland, but they are on Guðrún's doctoral committee.

"People living with more social justice do not need as much income as those living in less equal communities. From an economic point of view it is thus more economic, looking at society as a whole, to live in a more equal society as each krona there "buys" more welfare. The welfare sensitivity changes as well, that is how happy the individual is with each extra krona, in a more just society. This means that if we want a happier and more economic society we should prioritise a more equal distribution of income," explains Guðrún.

Their results indicate that the distribution of income is crucial. "The greater the inequality the higher the income needed to reach the same level of welfare as people in a more equal community. This means that you do not need as much to be as well off where the distribution of income is equal compared to where it is unequal. Furthermore, each krona buys more happiness, so to speak, where there is a more level distribution of income ," explains Guðrún.

She adds that existing research yielded similar results. Real income is of course important for peoples' happiness and welfare but is also crucial where they stand in comparatively. "The income of others people compare with influence how satisfied they are with their own income. The Easterlin paradox, that some might be familiar with, states that communities are steadily becoming richer however the level of welfare does not increase at the same rate as income. I find this interesting and I believe that comparison plays a vital part here, we tend to compare ourselves with the people around us. If my neighbour buys a new and fancy car it is not unlikely that it will influence how happy I am with my car," she says.

Happier and more economic society with a more equal distribution of income

Asked on the what the outcome means Guðrún says that the most important conclusion she draws from this part of her doctoral research is that equality matters. "People living with more social justice do not need as much income as those living in less equal communities. From an economic point of view it is thus more economic, looking at society as a whole, to live in a more equal society as each krona there buys more welfare. The welfare sensitivity changes as well, that is how happy the individual is with each extra krona, in a more just society. This means that if we want a happier and more economic society we should prioritise a more equal distribution of income.

Some may consider it unusual that an economics is tackling questions on happiness but the subjects are becoming increasingly diverse within this discipline and there is also Guðrún's unorthodox background. "I hold a Master's degree in ethics as well as in economics. Therefore I take great interest in the complicated relationship between theae two subjects many feel are on opposites poles. Which they are in some ways. I hope to get the opportunity to study the ethical parts of economics in the future or maybe the economic parts of ethics," she says.

Her work on the doctoral thesis continues and Guðrún says that in her second article of three she is focusing on the so-called equivalence scale. "This is used to measure household income taking into account the differences in a household's size and composition. It is generally assumed that the household income of two individuals does not need to be the double of a single home income to reach the same level of welfare. It is, however, not entirely clear whether the measurements generally used reflect reality. I will use European data to look at this."