A new study on risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries may have revealed a previously unidentified risk factor. This factor, which the researchers call “early peaks,” is more common in girls than in boys, and it has also been found that specific movements in the hips, knees, and trunk that often occur alongside ACL injuries also occur alongside early peaks.

“ACL injuries are an important research topic because the consequences of these injuries can last a lifetime. The causes of ACL injuries and the movements that increase their risk have long been sought, but with limited success. This study is therefore about identifying risk factors for ACL injuries so that they can be prevented in the future,” says Haraldur Björn Sigurðsson, associate professor of physiotherapy at the University of Iceland.

Haraldur explains that such research is challenging because many studies have been conducted in this area and many factors have been examined, but so far, the risk factors found in one study have not been confirmed in the next. “It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack. There are countless ways to analyse the data, making it statistically likely that something will come out as a risk factor purely by chance.” One possible explanation for the differences between studies could be that the data are not analysed systematically based on how ACL injuries occur. “By finding such a connection, it would be possible to significantly reduce the number of variables examined and thus reduce the likelihood of identifying a risk factor by chance,” Haraldur explains.

ACLs tear in one-twentieth of a second

“The idea for this study arose during my PhD, and it all stems from the question of whether movement analysis data could be examined entirely in light of what is known about the forces acting on the knee of a person who tears an ACL,” says Haraldur. Around 2016, there was a surge in research abroad on forces, including the development in the U.S. of hardware that could create ACL injuries in knees, mimicking those that occur in people. Around the same time, a group of researchers in Norway was analysing videos of ACL injuries with great precision using motion analysis software.

“These foreign studies showed that knee valgus, or the inward force on the knee, plays an important role in the injuries. They also showed that it happens extremely fast; an ACL tears in one-twentieth of a second from the moment the athlete’s foot touches the ground,” says Haraldur, pointing out that this speed makes studying ACL injuries so demanding. The key question was thus how to identify, during that extremely short period, a part of the movement that could lead to an ACL injury in a healthy individual.

Data processing methods at the heart of the study

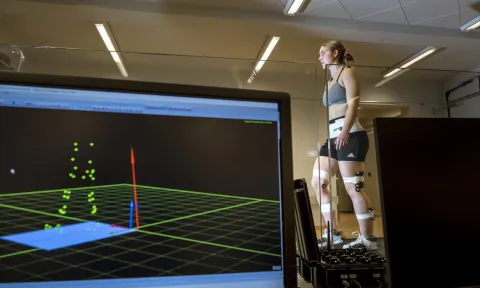

The research team uses precise motion capture equipment — infrared cameras that track reflective markers attached to athletes to analyse potential risk factors for ACL injuries. “The athletes then perform rapid and demanding changes of direction, which are the movements that most often cause ACL injuries,” Haraldur explains.

He says the data processing methods are at the heart of the study. “We calculate the forces acting on the knee, but although the equipment is good, it’s not perfect. In most studies, the peak values of the forces are examined, but this approach has major flaws because the peaks usually don’t occur as early in the movement as the ACL injuries do.” Even a slight shift in the reflective markers can significantly change the calculations, especially early in the movement, particularly with faster athletes. “To solve this problem, we developed a computational method that analyses the shape of the force curve at the beginning of the stance phase. The idea is that a certain shape, called early peaks, could be linked to ACL injury risk. It’s a shape where the peak knee valgus occurs early enough to align with when an ACL injury could happen,” Haraldur explains.