Unlike what is sometimes heard in public discourse, languages are not static but constantly evolving and changing. Language changes can occur, for example, due to societal trends and demands, the tendency to simplify linguistic systems or the influence of other languages. These changes also extend to how we pronounce words. Currently, Ásgrímur Angantýsson, a professor of Icelandic linguistics, is leading an exciting study with a large team of researchers on how regional pronunciation nuances in Icelandic have fared over recent decades.

“The research focuses mainly on the status and development of regional pronunciation features in Iceland and attitudes toward them. However, we are also keeping an eye out for signs of novelties in pronunciation,” explains Ásgrímur, who is co-leading the project with Finnur Friðriksson, associate professor at the University of Akureyri.

Mapping the current status

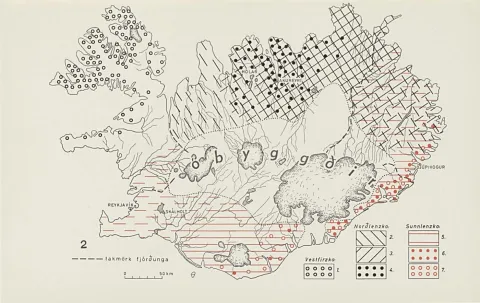

Well-known regional features include hard pronunciation and voiced consonants in the North; the Westfjords monophthongal pronunciation; southern hv-pronunciation, and the Skaftafell monophthongal pronunciation. Pronunciation variations more commonly associated with younger generations include ks-pronunciation, affricate articulation, and the so-called glottal stop pronunciation. Further explanations of these pronunciation features can be found later in this article.