Icelanders are fortunate in having written about themselves a short while after the country was settled. The fact that this material has been preserved is remarkable. This literature is of unique artistic value, and furthermore provides a glimpse into the lives of the people who wrote it; and insight into the cultural origins of a whole nation.

Torfi H. Tulinius is a professor of Icelandic mediaeval studies at the University of Iceland and leads the international master programme in the subject. He spends much of his time studying our medieval literature. This is important because “research in the humanities tackle the products of the human spirit, deepen our understanding of them, and open our eyes to their endless variety,” in the words of Torfi himself.

He asserts the sagas have long informed our understanding of who the Icelanders are. “Times change and Icelandic society has undergone more changes in the last century than ever before. We need to rethink our identity. One way to approach this is to revisit our literary legacy. Furthermore, this particular legacy is globally unique, with value that stretches way beyond our shores; thus understanding the Icelandic literary tradition enhances our knowledge of global literature.”

Searches for Trauma

Torfi is now scouring the stories of the original settlers in the sagas and Landnámabók looking for all signs of trauma connected to the settlement. This is not light material since the themes include enslavement, bereavement and loss of wealth and social status.

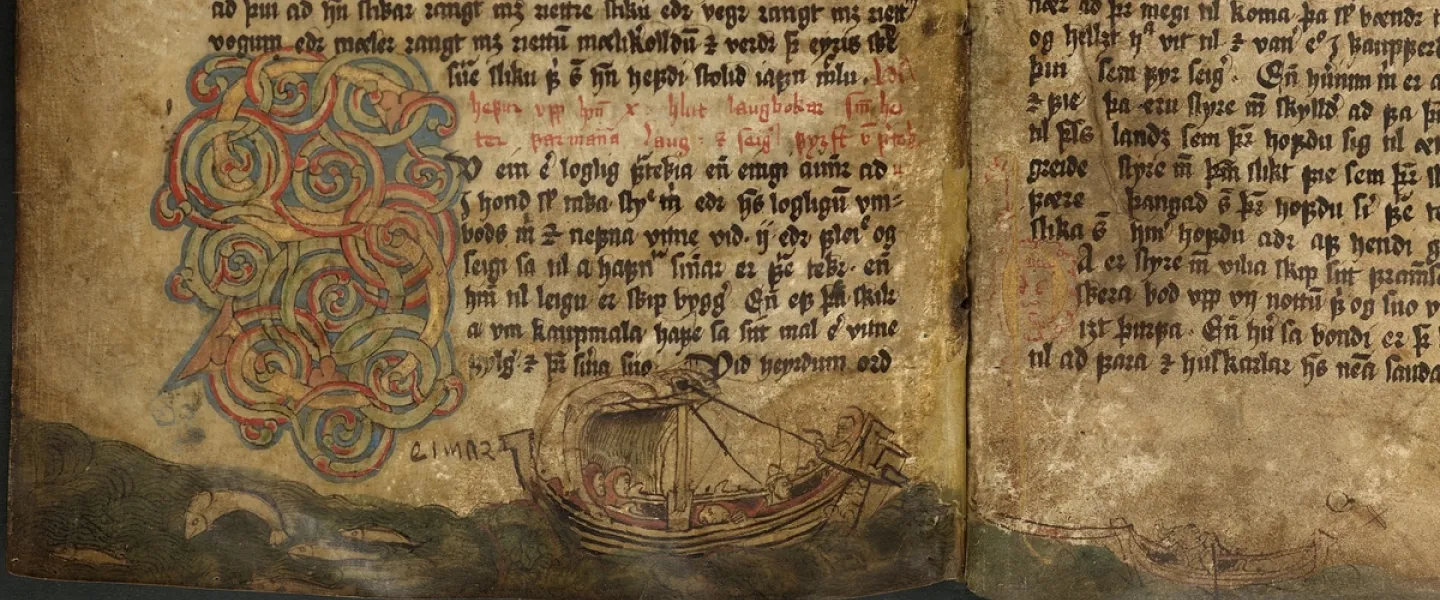

„These narratives are written more than two hundred years after the events themselves, but still give a certain picture of social circumstances in Iceland in the 9th and 10th centuries CE,” says Torfi. “However, they are a better source on how the authors and readers of the sagas in the 12th, 13th and 14th saw the past in the light of their own present.”

The traumatic societies that begat great literature

Torfi says that a lot in this literature indicates that the society that begat it struggled with a variety of trauma. The past that is sketched in the works is characterised by loss of homeland, social standing and even a good life in a fertile country.

“In the narrative of Landnáma and the sagas it often seems that the social standing of a person is determined by the location and extent of the settlement; or whether he or his forefathers has settled land or had to get land from former settlers. Social standing is thus at times lower than the character’s self-identity indicates. These stories from the past are probably told because they reflect the social realities of time of writing in the 13th and 14th centuries, not least the extreme violence of the age of Sturlungar.