The Arctic tundra has always been the domain of low-growing herbs and dwarf shrubs. Now this is changing as taller species are migrating into the tundra and existing species are growing taller. This has resulted in generally higher tundra vegetation over the last three decades reports an international group of 130 biologists in the journal Nature. Two Icelandic scientists participated in this study, Ingibjörg Svala Jónsdóttir at the University of Iceland and Borgthór Magnússon, at the Icelandic Institute of Natural History.

“We found that the increase in height didn’t happen in just a few sites, it was nearly everywhere across the tundra. If taller plants continue to increase at the current rate, the plant community height could increase by 20 to 60 percent by the end of the century,” says lead author Anne Bjorkman, at the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre in Frankfurt, Germany.

The harsh climate in Arctic and alpine tundra has limited the vegetation to low-growing plants. However, Arctic climate is now warming more rapidly than any other biome on Earth, which enables taller plants to migrate into the tundra and native plants to grow taller. The results reported in the article were reached by analysing the most extensive data set ever for Arctic plants. Data from over 100 sites across the Arctic and alpine tundra was included. The Icelandic participants contributed data from both Iceland and Svalbard. “The study shows clearly that the warming climate is the main driver of the vegetation changes,” says Borgthór Magnússon.

The study included several other plant traits than height, such as leaf size and nutrient content. These traits did not change consistently across the Arctic sites, but were more closely related to soil moisture than temperature. This shows that not only temperature variations but also changes in precipitation may drive future vegetation changes in the Arctic. “These vegetation changes can have long-term effects on biodiversity and ecosystem functions,” says Ingibjörg Svala Jónsdóttir.

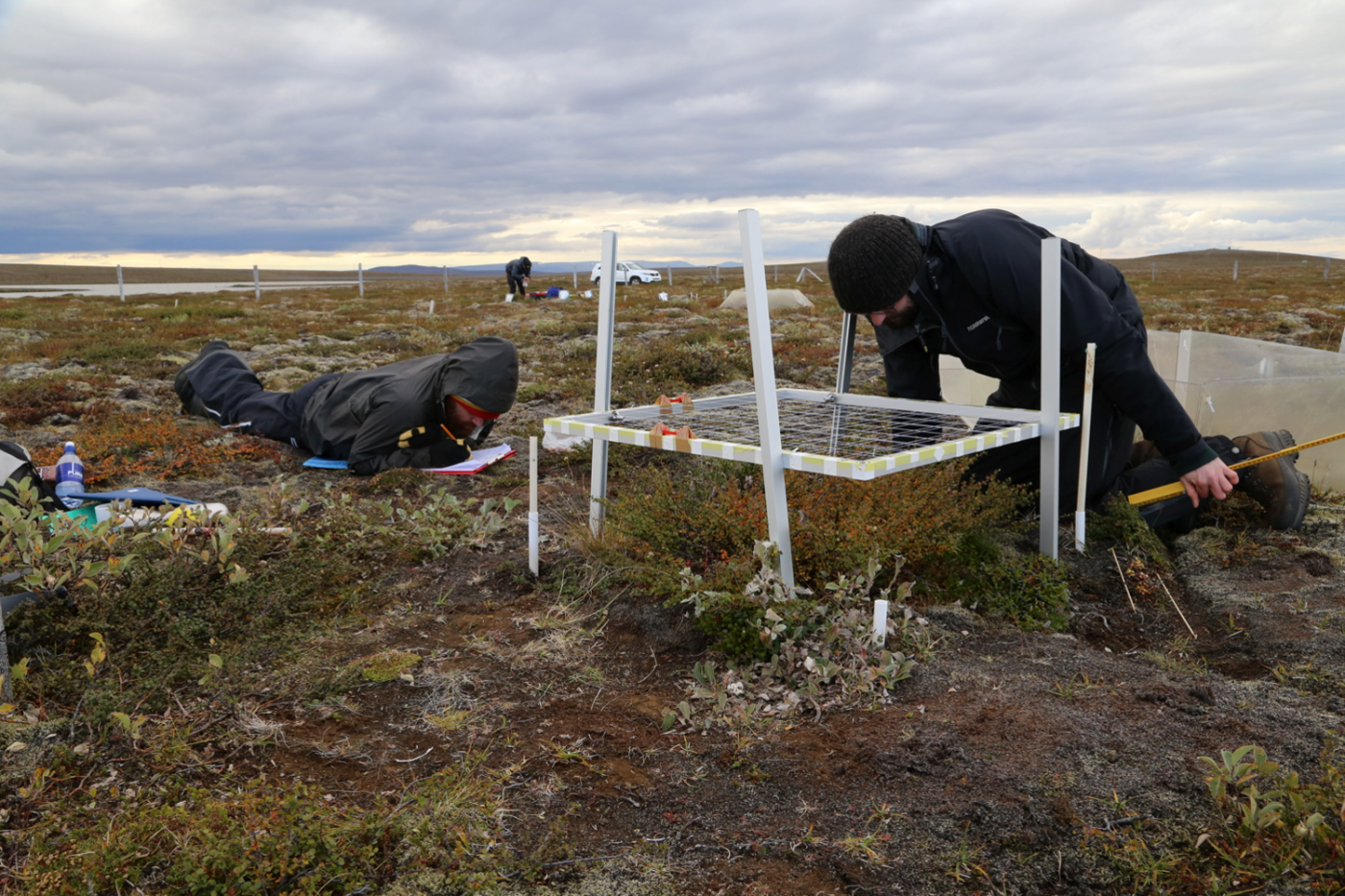

This study also demonstrates the value of long-term monitoring and international collaboration. A large part of the data included in this study comes from long-term experimental sites that were established in the 1990s within the International Tundra Experiment research network (ITEX) when two such sites were established in Iceland and ten years later in Svalbard under the leadership of Ingibjörg Svala Jónsdóttir. Data from several long-term sites set up in Iceland in 1997-1998 to study vegetation composition and the condition of lowland and upland pastures were also included. The project is run in cooperation by the Icelandic Institute of Natural History, the Soil Conservation Service and the Agricultural University of Iceland and led by Borgthór Magnússon. “As a next step it is important to understand how grazing by tundra herbivores, including livestock, interact with the changing vegetation in warmer climates” says Ingibjörg Svala Jónsdóttir.